Arts & Sciences Research Paper #25: The tools of Elizabethan clothing: Sheep to garment

Our twenty-fifth Research Paper comes to us from Lady Astriðr Musa of the Barony of Concordia of the Snows. Her reconstruction of a late-period garment has led her into a deep look into the tools of Elizabethan clothing, which she is here to share with us! (Prospective future contributors, please check out our original Call for Papers.)

The tools of Elizabethan clothing: Sheep to garment

Table of Contents

Introduction

Beginning with the Sheep

After the Shearing: Preparing the Fiber

Narrowing the Focus: Spinning into Thread

From Many Into One: Weaving the Cloth

Into Three Dimensions: The Tailor’s Tools

Conclusion

References

Introduction

To understand the garments of any time period, it can be useful to investigate the methods of manufacture, and the tools used to produce them: from the original fiber to the finished garment. The study of tools and processes not only tells us more about the garment itself, how it would have functioned, its value, etc.: it can also give us insight into the lives of the people living at that time. I engaged in this type of active study in my recent recreation of a men’s Spanish style cloak, and have compiled some of the research on the process and tools here.

Beginning with the Sheep

By the 16th century, a focus on sheep breeding across Europe had resulted in a wider availability of differing qualities of wool. Although the most common sorts of wool still contained some longer coarser fibers, the older primitive breeds, with their double coats, had by and large gone and the trend towards to modern breeds was well established. (Even the finest wools available at the time, however, would not have been as fine as modern merino.) English wool, prized for its quality, was available mainly in white but also in other natural colors (Blair and Ramsey, 320). Although in rural areas and among the lower classes cloth production for clothing was still done in the home, cloth production had become the foundation of the economy in many places. The export of fine English wool was a huge source of revenue for the English crown, while fabric production was the linchpin of the economy in the Low Countries and Venice (although by the 16th century, Venice was turning more and more to silk instead) (Braudel, 312-17).

For a high-class item, the material would almost certainly not have been manufactured at home, but in a shop. Many such shops existed in the fabric producing centers of Europe, working on the model of Verlagssystem, or “putting out system”, run by entrepreneur businessmen who managed the work. Some of them sent out parts of the work to independent contractors, while others managed it all under one roof. Venetian records show shops employing from 8 to upwards of 100 employees (Lanaro, 224-26). The work itself was still not very mechanized, although larger buildings could house larger looms and streamline the process.

Swanenburg’s painting above shows a workshop in 1595 where you can see the wool preparation, spinning, reeling, and the use of a warping mill.

Fiber would have been obtained and picked, then combed or carded depending on staple (the length of the fiber) and intended use. It would then be spun by the spinners, measured, warped, and woven. After being taken from the loom, fabric would have been fulled, possibly dyed, stretched, sheared and possibly brushed to raise nap. All this was done in much the same way hand weavers go about those same tasks today, albeit on a larger scale. We know these processes existed even in the industrial production of cloth, because by 1539, at least in Venice, the workers had their own guilds which left records (Lane, 313).

[Back to top]

After the Shearing: Preparing the Fiber

Fleece would have been obtained for the mill sorted by grade for different kinds of cloth (Blair and Ramsey, 323). Just so, modern spinners choose different fleeces for their desired outcome. Period wool would have been washed on the sheep before shearing, then the sheep would have been penned on clean grass for enough time for the lanolin to work back through the wool, then sheared and the wool processed. The lanolin acted as a lubricant for combing.

Once the fiber was sheared, it was baled, sold, and transported to the mill, where it would usually have been processed via carding or combing. After the introduction of cards in the 14th century, carding became the preferred preparation for fine wools to be used for the spinning of woolens (spun from the fold) while combing was still used for coarser longer staples to be spun as worsteds (spun from the ends) (Blair and Ramsey, 323-24).

[Back to top]

Narrowing the Focus: Spinning into Thread

After the carding, spinning. (Take a look at this handy guide to the mechanics of a spinning wheel, and here for detailed video explanations.) By the latter half of the 16th century crank operated wheels and flyer style wheels were in use for flax and wool (as seen in paintings, particularly from the low countries) although the use of hand operated spindle type wheels persisted for wool spinning through the next century (as is documented by my own circa-1700 great wheel). The first appearance of the flyer on the wheel is in a picture dated 1475-80, in the Mittelalterliches Hausbüch of the Waldburg family, from the southern part of Germany (Baines, 85). The addition of the modern treadle to the wheel is harder to pinpoint. Most 16th century images show a hand crank wheel with a flyer, but treadle wheels, almost indistinguishable from modern models, are appearing regularly in artworks in the first half of the 17th century. Ultimately there seems to be no concrete evidence of a treadle run wheel prior to the 17th century, but after that point images begin to appear either including the treadle itself or showing spinners using two hands, from which the presence of the treadle can be assumed even if it is not visible (Baines, 92).

This presents a difficulty for the modern spinner attempting to follow historical practice: all readily available modern wheels which use a flyer (which not only is a more efficient system, but tends to produce more even and stronger threads) are fitted with a treadle. Perhaps a saxony style wheel could be fitted with a crank to simulate the experience of a period wheel. However, I would argue that it is suitable to use modern wheels (particularly those with double drive band tension) for thread produced for items dated post-1475 as the most significant upgrade in speed and difference in technique is dictated by the flyer and not by whether the wheel is spun by hand or by foot. Especially for fiber artists using the long draw technique, as used on a walking or spindle wheel, there is very little difference in end product or even manual technique, since, extrapolating from walking wheel spinning, one hand can likely be taken momentarily from the crank to assist in drafting without stopping motion of the wheel.

[Back to top]

From Many Into One: Weaving the Cloth

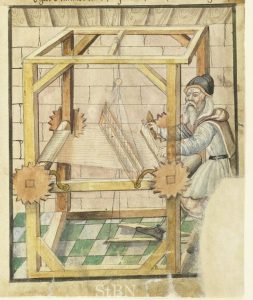

By the 16th century, horizontal shaft and gear driven looms were in full use, edging out vertical looms where the warp was held straight by weights (“warp-weighted”), and although they didn’t look much like our modern jack looms, they used the same technology and the same processes.

Unfortunately many of the images available are not laid out to give us a clear picture of the rigging of the loom, but the image above looks very much like a counterbalance loom (note the pulley system above) in which all shafts move either up or down with the depression of the treadle, depending upon how the tie up is done. (Watch a video here of weaving in action on such a loom.)The rising shafts create the pattern, but moving the threads in both directions is advantageous in that it allows you to weave further before advancing the fabric onto the cloth beam, and it evenly stretches all the threads, reducing wear on threads. This particular gentleman is weaving plain tabby, with only two harnesses, but the weavers of the 16th century were masters of their craft. While looms comparable to modern handweavers’ looms were used for most woolens, the great silk looms of Italy (some of which still run today) were the first muttering of mechanized fabric production, with punched wooden cards dictating which of the many shafts rose and creating magnificent patterns.

For woolens, fulling the fabric would have scoured it of all remaining oils and sizing, softened it, and closed the structure of the weave. It could be fulled anything from lightly, producing a soft cloth with a visible weave structure, to heavily, producing weatherproof felt-like fabrics. Although in many rural areas (right up to the modern era!) this was done by groups of women working together, pounding the fabric against a waulking board to the rhythm of song, by the 11th century most of the work was being done in water-powered fulling mills. There camshaft driven hammers pounded the wool against a textured surface, the whole submerged in water and washing agents such as fullers earth, soapwort, or stale urine (Gimpel, 14).

At this point the fabric could be diverted to the dyers, to be made into colors in the great dye furnaces, or left as was. The fulled fabric would have been stretched onto a rack, tensioned by tenterhooks (hence our phrase “on tenterhooks”) to dry. This blocked the fabric, removing any wrinkles and irregularities caused by the fulling process. Once it was dried, it could be further refined by shearing to remove unwanted nap and show the weave pattern, and/or brushed with combs full of teasels to bring up a soft nap.

[Back to top]

Into Three Dimensions: The Tailor’s Tools

The finished cloth would have been sold to either the end consumer, or to a professional tailor. The tailor’s tools available during the 16th century were not so different than our own, although the form may have varied slightly from the modern. They measured, marked, cut, pinned and sewed much as we do now.

Steel needles were available during this period, although the method of making them seems to have been something of a great secret. They may not have been generally available, although they would have been used by any who could afford them. It is thought that the meteoric rise of fancy embroidery during this period may have been in relation to the improvement of needles (Leslie, 130). Considering the long history of incredible embroidery I don’t know how much credence I give this theory, but it is certain that this era of history featured extravagant embroidery on almost every available surface, and a good needle is an invaluable tool. Every modern seamstress has her favorite needles. Needles are much rarer in the archaeological context than pins, partially because by this time steel and iron were more commonly used, and neither survives well, and probably partially because they were so expensive, and therefore taken care of much more carefully, as the prevalence of extant needle cases suggests (Beaudry, 44, 46).

The manufacture of the time produced needles with a flattened steel head and round punched eye, rather than our modern oval-shaped long eye (Beaudry, 48). Steel needles required a knowledge of metalworking that didn’t come to Europe until relatively late. Indeed, the first needle manufacturer in England dated to about 1550 and was set up by refugees from Flanders, using a nearly 20 step process (Beaudry, 47). Needles were available before this from manufacturers in Spain, and in fact, for a time, steel needles were referred to as “Spanish needles.”

The handmade needles of the period probably varied in size rather more than the later machine-made needles, and there is less record of them. The extant examples tend to be rather larger in size, and likely were intended for heavier work. It is thought that the finer hand sewing needles have mainly not survived the years (Beaudry, 80). That said, likely speculation leads us to think that period needles would not have been quite as fine as the machine made needles available now, and probably varied in size and style by use just as they do now. A tailor in 1657 was listed in his will as owning a needle case and 4 needles. One can imagine they could have been in an assortment of sizes for different types of work. (Look at some of the super fine stitching on body linens and you know they can’t have been using awls for the work!)

The quality of pins improved along with the quality of needles. They would have been typically made of brass, and with either a metal ball or flattened head made of a separate coil of wire, soldered on with tin, and then stamped smooth to avoid snagging on fabrics (Beaudry, 16). Pins were referred to by a vast and confusing lexicon of terminology, but the most common sewing pins seem to have been referred to as “short whites” by pin makers, and to have been a little over an inch long and about a 1/16th of an inch in diameter (Beaudry, 24-25).

Linen and silk thread are listed in wardrobe inventories, both natural and colored (Hayward, 351.) Silk thread would have been easily dyed to match for visible stitching, but likely not for structural stitching, as it cuts through woolens over time, something that period tailors would have known. Although linen thread presents the eternal problem of dying plant fibers, Henry VIII’s wardrobe information lists colored thread separately from colored silk, so it was available (Hayward, 350). Wax may have been used on some threads at the taste of the tailors. It is missing from some great house inventories, where things like thread and pins are included, but remnants of it do appear on extant garments (Hayward, 350).

Scissors and shears were employed, and neither has changed much in form or function, although modern materials and manufacture are certainly different. The tailor’s shears in Giovanni Battista Moroni’s painting, look very much like my pair made by Gingher, aside from the leaf-shaped blades. Small scissors were also available for small jobs like trimming threads.

For us in modern culture, these items (excepting the tailor’s shears, which are still an investment) are common, almost throwaway. I am fussy about the quality of my pins and needles, and so purchase them at the more expensive end of the scale. Even so, it’s no fuss if some are lost. I purchase a new, large box of good quality glass headed pins every few years without thinking about it. This would not have been so at the time this cloak was made. For perspective, at the end of the 15th century, a sheep cost 20 pence, and a paper of 100 pins cost 4p (Beaudry, 16).

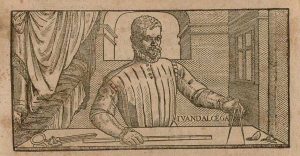

To make the final garment, the fabric would have been marked and cut from a tailor’s draft (an image in a book of patterns, enlarged to individual measurements), or from the knowledge of the tailor, and specifically to either the draft or to the person’s measurements. The woodcut above shows master tailor Juan De Alcega marking a garment. He uses a marked straightedge and a compass, and you can see a pair of shears and a marking tool beside him. I could not find accurate information about what 16th century tailors used to mark their fabric: but modern tailors’ chalk, composed of wax, pigment, and chalk, would certainly have possible to make.

[Back to top]

In Conclusion

In modern times we see the making of garments as either a domestic skill, or a niche market: only the very wealthy can afford custom tailored work. The tools used for handwork are disregarded, and cheaply mass produced. The study of historical tools and methods, following the process from sheep to finished garment, can take us outside this modern paradigm, and help us understand a time where fabric, clothing, and the supporting manufacturing industries (and the powerful guilds responsible for them) were the foundation of the wealth of nations. In the 16th century’s fabric-supported economies, clothing was a status symbol similar to today’s Rolex watch or Rolls Royce, and the supporting trades such as pin- and needle-making were lucrative in their own right.

Working through this process from beginning to end to make a garment has given me a new understanding of both the value of clothing in the 16th century society, and a great respect for the masters who made it. The very fine wools we see in extant garments were all made with these tools. I made a relatively coarse utilitarian fabric, and it really pushed my skillset. The idea of creating the superfine woolens from the historical record in this manner is somewhat daunting (I still want to try it though!). You can see why people specialized in individual parts of the process, and why long apprenticeship was so important. One of my conclusions from this study was that late-period fabrics probably didn’t behave much differently than modern machine-wovens (assuming similar thread count and structure), but the process of creation and the way it impacted the creators and their daily lives was certainly far different.

[Back to top]

References

Baines, Patricia. Spinning Wheels, Spinners and Spinning (Robin and Russ Handweavers: McMinnville, Oregon, 1976).

Beaudry, Mary. Findings: The Material Culture of Sewing (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2006).

Blair, Jon, and Nigel Ramsey, eds. English Medieval Industries: Craftsmen, Techniques, Products (Hambleton & London: London, 1991).

Braudel, Fernand. The Wheels of Commerce; Civilization and Capitalism vol. 2 (Harper and Row: New York, 1982).

Gimpel, Jean. Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages (Pimlico: London, 1992 reprint [1976]).

Hayward, Maria. Dress at the Court of King Henry the VIII (Routledge: London, 2007).

Lanaro, Paolo, ed. At the Center of the Old World: Trade and Manufacturing in Venice and the Venetian Mainland, 1400-1800 (Victoria University/University

of Toronto Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies: Toronto, 2006).

Lane, Frederic C. Venice: A Maritime Republic (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, Maryland, 1973).

Leslie, Catherine. Needlework Through History: An Encyclopedia (Greenwood Press: Westport, London, 2007).

[Back to top]