Pennsic Arts and Sciences Champions

The Gazette thanks the King’s Champion of Arts and Sciences, Lady Raziya bint Rusa, for this report.

The East Kingdom’s team of artisans displayed a wide array of fabulous skills at the Pennsic 46 Arts and Sciences War Point. Below, we are pleased to provide some highlights of their work.

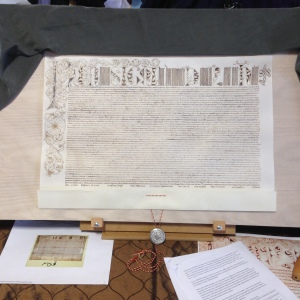

The reference document was a papal bull, and was chosen for its complexity and topic. The original has about 1850 words, and is the charter for St. Mary’s College. In addition to the reference material having clear parallels in use, the concept of a deliberate forgery is medieval.

Many medieval organizations would write up charters after they were established, because they needed a document to prove legitimacy. This was done despite the fact that the documents may not have been required when the organization was founded. The East Kingdom College of Scribes is in a similar situation, with no royal charter on record. This charter was not made to be an official charter, but instead to translate the concept of an official forgery to Society culture.

The charter itself is very similar to the original but not an exact copy. The scale is smaller because of the cost of parchment. The ink is walnut instead of black keeping with the ink of the original.

The text has undergone small changes in order to make the references to SCA culture, instead of the Roman Catholic Church. The beginning and ending lines have likewise been changed to note that the document is not official, and the date is written to society standards. Some of the changed lines now read (in translation): “By the order/request of the Signet, this document has absolutely no legal standing. In fact, this document should not be taken seriously.”

This dress was made as an imitation of a wealthy noblewoman’s gown, and as such is fairly sumptuous. It is not as ornamented or as expensive as that of the queen. The garment is made of silk and linen and contains artificial pearls and metal accents.

The outer dress is red silk with white silk lining the tippets; linen lines the rest of the garment. The most expensive fabric is used on the most visible areas, and more utilitarian fabric is used elsewhere. This is an appropriate medieval practice that was deliberately duplicated here .

Internal non-visible seams were machine sewed to save time, due to time constraints. All visible seams were hand sewed, and can be seen in the felling of the body seams. The dress is covered in 36 “pearled” roses. Each rose took approximately a half hour to create.

The apron and samples of Reticello on display are based on 16th Century Italian lacemaking. This project was made more difficult to research because the all extant examples of the craft are later than 1600, despite confirmation that the craft occurred before 1600.

Reticello is the earliest documented form of needle lace. The process involves removing threads from the construction of the fabric and binding the remaining threads together into artistic patterns. The challenge arises from engineering the product to be both beautiful and structural.

The apron is made of 4.5 oz Barry weight weight linen with 60/2 linen thread for the lace. It has 23 2″ squares of reticello lace in a line through the lower part of the garment. Each square takes approximately 6-8 hours of work. Not including the sewing, or practive, this accounts for 138-184 hours of labor. There should be three additional vertical lines of lace on the apron to be more accurate to Italian aesthetics. The lacing was limited due to time constraints.

This piece is made as a copy of an extant silver example from a Swedish museum. The armring was for a woman and likely dated to the 8th century.

The ring was constructed carefully because, due to cost of materials, there would not be an opportunity for a second chance at making the armring. 30″ (8.5 oz) of sterling silver bar were required to make the piece. Sterling was used instead of pure silver, because medieval silver was not very pure.

Practice for the final work was done in copper, although copper has significantly different properties when working. Silver melts quickly – a property which almost resulted in the loss of the piece.

The piece required forming by hammer, annealing, twisting, polishing, and stamping. The stamping was made with a tool that had two triangular shapes on it. The squares on the final product are the negative space left over between the stamped impressions.

The laurel wreath was created in the style of wreaths seen in illustrations in the 14th Century. No surviving laurel wreaths from that time have been found, but older Greek and Roman versions exist. Given the context of one illustration – gold leaves, the brittle nature of real laurel, and the presence of the leaves upon an emperor – the assumption is that the illustration depicts a metal, rather than a real wreath made of the laurel plant.

The wreath was made of brass rather than gold, due to finanical concerns. Sheets of brass were soldered to wire in pairs; each pair was then attached to a spine. The brass pieces were so thin that several wore through during construction and had to be remade. Embossing veins on the leaves was done with fingernail and blunt pencil.

In period this kind of work would have been done with an alcohol blow lamp; this piece was made with a propane plumbers torch. A mix of ash, sand, and pumice in a matrix of wax and oil would have been used to clean up the marking and flux from construction. It would have been manipulated with sticks when applied to the metal; in this case a modern dremel with scouring pads was used because of time constraints.

NB: All photographs of the exhibition graciously provided by Mistress Anastasia Gutane.