A&S Research Paper #30: Warding Off Plague and Other Miasma with Pomanders

Our 30th A&S Research Paper comes to us from Tiffan Fairamay, who resides in the Province of Malagentia.

In this paper she takes us through the history of Pomanders, discussing the symbolism associated with them, as well as details about the time, location, and purpose of their use in period.

Tiffan also keeps an A&S blog where information about how to make a pomander can be found, along with detail and images of her own pomander creations.

Warding Off Plague and Other Miasma with Pomanders

Tiffan Fairamay (MKA Sylvan Thorncraft)

Introduction

My objective when I started this project was to experiment with period ingredients to make a pomander of my own. There were so many aspects of pomanders that I found appealing: the long list of exotic, esoteric, and decadent ingredients… the alchemical process of making them… their taboo nature as ward against sickness and death, especially considering the devastating scale of the Black Death… the beautiful, spherical cases that carried them… All these things helped pique my initial curiosity.

As is often the case, the deeper I dug, the more rabbit holes there were to explore. Soon I was looking at how trade relationships connected Europe to Asia and Africa… medieval thoughts about how health was maintained and how disease proliferated… details about commonly used ingredients, where they came from and what other ideas medieval Europeans had about these substances… as well as the powerful and often paradoxical fascination that many medieval Europeans had with fragrance. This paper will discuss the history of pomanders, while information about how I have made a modern version can be found on my blog, link above.

Context: What was Daily Life Like?

It may not be possible to understand the significance of pomanders without an appreciation for the importance of fragrant substances to Medieval Europeans. Ian Mortimer, author of The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England, offers many vivid descriptions of what it would have been like to visit 14th century England, including this passage about arriving in Exeter, or any other city or large town of the time:

“Arriving in every one of these places involves an assault on all the senses. Your eyes will open wide in at the great churches, and you will be dazzled by the wealth and the stained glass they contain. Your nostrils will be invaded by the stench from the sewage-polluted watercourses and town ditches. After the natural quiet of the country road, the birdsong and the wind in the trees, your hearing must attune to the calls of travelers and town criers, the shouts of labourers and the ringing of church bells. In any town on a market day, or during a fair, you will find yourself being jostled by the crowds who come in from the country for the occasion, and who live it up rowdily in the taverns. To visit an English town in the late fourteenth century is a bewildering and extreme sensory experience.”[1]

With this description in mind, Paul Freedman’s words from his book on Medieval spices, can help us start to appreciate the difference between a modern ideal of non-smell, the absence of scent, and the medieval mindset, where people sought out wonderful smells as a way to avoid the awful smells that filled daily life.

“… excrement, animals, sickness, sweat, dirt, the effects of such noxious enterprises as tanneries or smelters. It is precisely because of this inevitable familiarity with awful odors that people in premodern societies were entranced with beautiful smells. They experienced a wider spectrum of olfactory sensations than we are familiar with, both good and bad.”[2]

How to Stay Healthy – Corruption of the Air

Explaining the source of illness and reasoning how to avoid falling sick were just as important to people then as now. Mortimer reminds us that in the 14th century “The most common cause of illness is, according to most opinions, divine judgement.”[3] He goes on to explain that this is why it was so important to people of the time to first seek a religious cure, before employing a medical one. After all, how could there be any hope of a medical cure being effective, if you weren’t in alignment with Divine will?

However, other factors were also considered when explaining the origin of disease. The word miasma was first used in the 17th century to describe an unhealthy smell or vapor, but the commonly held idea that illness and disease are caused by the dangerous influence of bad, pestilential air dates at least to ancient Greece and the work of 2nd Century physician and philosopher Glaen. Plague tracts written in 1348 by Spanish physician, Master Jacme d’Agramon, and the medical faculty of the University of Paris blame the epidemic on air that has become corrupted. Jacme’s tract describes in detail the different qualities of air and how air becomes corrupted. The tract from the University of Paris also suggests using incense and fragrance to prevent putrefaction of the air and remove corruption. A year later Spanish-Arab physician Ibn Khatimah came to a similar conclusion in the tract he wrote.[4]

While plague was caused by corrupt air, the corruption of the air was thought to be caused by dangerous natural factors, like astrological influences, fetid air and vapors from decaying vegetable or animal matter (including human corpses), and gaseous exhalations from swamps, marshes, and stagnant water, as well as gasses released from the earth during earthquakes.[5] This bad air was carried by the wind (especially winds from the south), and would enter people’s bodies through pores in the skin where it would upset the balance of the humors (four substances believed to control the body’s functions), causing people to fall ill.[6]

Considering the visceral relationship people had with smell on a day to day basis, it is easy to understand how the medieval concept of pestilential air and its relationship with disease and maintaining health would have made so much sense. If a bad smell reveals a dangerous presence in the air, then great care would need to be taken to protect oneself from these malevolent atmospheres.

The Importance of Symbol and Association

And so, quite logically, if bad smells indicate that illness is present, or are themselves the cause of illness, then good smells must have some inherent goodness to them. This notion is revealed in the medieval Christian belief that “what is holy shows itself by fragrance.”[7] Though some ingredients incorporated into pomanders certainly did not smell “good”, most did, and by medieval estimation fragrant pomanders would have been valuable medicine indeed.

To the medieval mind, pomanders may have been thought to work in ways that went beyond their fragrance. In Perfumes and Pomanders, Launert states that pomanders also probably functioned as amulets, and that both the container and its contents had “apotropaic significance”, and were used to ward off evil. He notes that “Not infrequently pomanders were worn along with other amulets…”[8] or were encrusted with precious stones that also were known to have healing and protective associations.

Doctrine of Signatures

To understand how substances and materials gained these associations with various healing and protective properties it is helpful to understand the Doctrine of Signatures, an idea which also dates from the time of Galen, and featured prominently in medieval European medical practice. The Doctrine of Signatures compares the shapes and colors of different plants and animals with organs and parts of the human body to determine what healing properties these plants and animals might have.[9] The Doctrine of Signatures may have helped determine what ingredients to include in pomanders, as well as their shape. Though much less common, pomanders in the shape of snails “have a symbolism of their own… The ability of the snail to withdraw into its protective shell at times of danger or hardship resulted in its becoming the symbol of spring and resurrection. We know of the apotropaic use of snail amulets when plague was rife.”[10]

Talismans and Reliquaries

Thinking about pomanders as a type of amulet, we can start to appreciate that the mere presence of medicinal plants and substances was thought to provide protection and healing, sort of like a lucky charm. In this way, the pomander may contain different substances depending on the healing effect desired by the person who would carry it.[11]

In modern secular society, it can be difficult for some of us to imagine the degree to which religion suffused daily life in medieval times. Keeping in mind the importance of using religious cures before medical ones, it seems useful to examine how people of the time felt about religious relics to help us understand how they could also come to rely on these and other materials to convey healing and protective qualities.

Devotional practices and proximity to relics were thought to connect one to the Divine. The practice of linking natural objects to the supernatural and assigning healing power to devotional relics as well as plant, animal, and mineral material (as described above) is a very old, and cross cultural human practice.[12] Early examples of pomanders may have combined religious keepsakes and fragrant plant material, like the small book shaped pendant “filled with magical aromatic herbs and/or devotional relics”[13] found in a 6th century, Hungarian woman’s grave. Even though pomanders were used much later, the examples that we find being used as part of a rosary seem to directly combine the elements of prayer, devotion, and healing substances.

Spices

Spices and Healing

Many factors and ideas contributed to the mystique of spices, and exploring some of these can help us appreciate why including spices in pomanders could be thought to offer protection beyond their lovely smell. Freeman notes that the Garden of Eden was thought to be the true home of spices, laying a foundation for the notion that spices are sacred and other worldly.[14] Building on that, most Christian geographers of the time felt that paradise, or heaven, was located in the East. From this perspective, spices were mysterious, expensive and exotic because of their distant origin and the extensive, dangerous trade routes required to obtain them, as well as sacred and magical because of their origin in the East, the direction of heaven.[15] Even though wearing fragrance on the body itself was discouraged by the Church, which viewed adorning oneself in this way as immodest, there was a long tradition of the use of fragrant resins as incense in religious rituals, and it was thought that one way to confirm a person’s sainthood was by the “marvelous sweet odor” revealed by their body after death.[16]

In addition to these holy qualities, medieval medicine thought that spices themselves were good at balancing the four humors, or influential fluids, of the body. One’s health depended on the equilibrium of the humors, which affected the wellness of body and mind.[17] This made spices a potentially valuable tool for healing.

How European’s Obtained Their Spices

It is interesting to note that even though spices were incredibly popular and used in great quantities in medieval Europe, “the spices that arrived in the eastern Mediterranean to supply the European market were a small part of the global trade in these commodities.”[18] Europe was on the western edge of a trading network that’s heart was located in India. Except for Marco Polo’s journey, Europeans seem to have had little direct contact with the lands of the east before the late 1400s. Instead, they relied on “Arab traders and travelers who had the experience and knowledge to understand nearly the entire sequence of the spice trade.”[19] These traders were themselves part of large loops of trade, most of which were centered in India. Merchants from Mediterranean Europe brought spices from Alexandria and other eastern ports to spice trading hubs like Montpelier and Nuremberg.

It would have been reasonable for spices to command a high price in the market because the actual journey people made to bring them to Europe from their native lands was long and arduous, passing through many hands at many ports. But traders and merchants at the time justified even higher price tags by encouraging the common belief that many spices were guarded by poisonous serpents and other monsters, or grew in dangerous, inaccessible places. “When it isn’t really known where a valued commodity comes from, this mystification is all the more plausible, tempting, and attractive.”[20]

Finally, the European consumer would have had access to these exotic substances by trading with a spice merchant at an apothecary, or a traveling peddler in more rural locations. “The medieval spice merchant or apothecary seems to have handled several kinds of products whose relation to each other is not all that clear: edible spices, medicine, sweets (including medicinal preparations but also candied fruit, sugar-coated nuts and spices, nougats, confectionary of all kinds), cordials (spiced and fortified wines), wax (candles and sealing wax), paper, and ink.” Candles were also considered medicine of a sort, since they were lit during prayers to aid in healing.[21] The only thing that these items seem to have in common is that they are special, delightful, and rare.

Pomanders

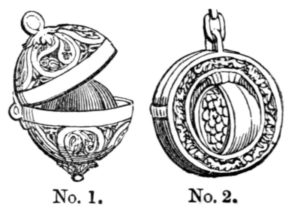

Long before and throughout medieval times, burning resins and herbs as incense for spiritual and healthful purposes was common and well known. Carrying fragrant solid or semi solid substances was one way people created a scented atmosphere around themselves. Liquid perfumes were not used until the 17th century, so people of the western world used fragrant solid or semi solid substances if they wished to create a scented atmosphere around themselves.The term pomander comes from the French: pomme d’ambre, in which pomme describes anything apple shaped, and amber means ambergris, or perfume in general.[22] The word pomander came to refer to the fragrant substance, or the intricate case made to hold this substance. All early pomander cases were made to hold a “single mass of solid aromatic material. They were spherical in form, or almost so, and usually opened into two equal halves by means or a hinge around the “Equator”. The two halves were usually held together by a spring release device. At one pole they had a loop and ring and at the other a decorative knob. Only when they were part of a rosary did they have a ring at both poles. The surface between equator and poles showed pierced decoration, from simple gothic tracery, flower heads, fish bladders, and medallions within tracery to fine filigree work with plant motifs.”[23] Artwork from the time shows us that the loop allowed a pomander to be hung from one’s girdle or neck. Others were attached to a ring with a much shorter chain, and held in the hand, or worked into rosaries, and later, buttons and other clothing decoration. Keeping the pomander close at hand was important because handling it warmed the resins, musk and spices, which helped release its fragrance.

These simple, perforated, metal balls, eventually led to ones of more complex construction, with hinged segments so they open like segmented fruit, each compartment holding a different fragrant element.[24] One 16th century German pomander has spaces labeled for: canel (cinnamon), negelren (cloves), muskat (nutmeg), schlag (a composite of ambergris, musk and civet), bernstein (amber), and rosmarin (rosemary).[25] Though the apple or knob shaped pomander is certainly most common, later in period and after, pomanders were also made into the shape of snails, skulls, books, hearts, and more.[26]

The ornamental metal ball wasn’t the only form of pomander. Alternately, George Cavendish gives us a wonderful contemporary description of Cardinal Wolsey using a hollowed orange rind which had been filled with a sponge soaked in vinegar “and other confections against the pestilent airs; to which he most commonly smelt unto, passing among the press, or else when he was pestered with many suitors.”[27]

Time Period of Use

Pomanders had enjoyed a long history of use in the Arab world by the time they arrived in Europe. Though a very early pomander of oriental origin was found in the tomb of a 6th century German prince, and later one was presented to the crusader Emperor Frederick Barbarossa by King Baldwin of Constaniople in 1174. [28]

Pomanders appear to have become more common after the 1348 wave of the Black Death, though Soden-Smith offers us a reference to an unusually early poume de ombre, or scent ball, made primarily of ambergris from between 1319 and 1322 that appears to have belonged to Margaret de Bohun, daughter of Humphrey de Bohyn.[29]

Intricate silver and silver gilt pomander cases were crafted from the 14th through the 17th centuries. There are also many portraits from that time depicting people with rosaries including what may be pomanders, but it is difficult to tell from these paintings if the rosary is featuring a large decorative bead or a pomander.

Some scholars say that the pomander had fallen out of fashion by the 17th century in favor of liquid perfumes, like scented vinegars.[30] Others feel that it wasn’t until the 18th century, when smelling boxes overshadowed pomanders.[31]

Class and Accessibility

Their expensive ingredients and extravagant cases meant that pomanders were often medicine for nobility and the upper ranks of the clergy. Freedman reminds us that spices were highly esteemed and passionately desired by medieval Europeans. But to be effective status items, these exotic and expensive substances needed to be consumed publicly. “[…] all of these spices, jewels, potions, and electuaries were luxury items as well as medicines. Medicine remains expensive today, certainly, but no one leaves their prescription drugs out on the piano or coffee table to display their good taste and ability to afford them. [… In medieval Europe] the boundaries between wellness and luxury were nonexistent.” [32] Some pomanders were richly decorated with jewels and pearls, and were “a favoured form of gift from one [person] to another…”[33]

Pomanders were also made of less expensive ingredients. “Doctors distinguished between herbs and exotics and acknowledged that their practice was to prescribe modest local ingredients for the poor and fine expensive spices for the rich,” [34] even though it is also acknowledged that herbs often work just as well, if not better. When it came to pomanders, sometimes these more affordable options were “less agreeable […] for example finely sieved earth mixed with scented substances, and held together with gum or other plant secretions.”[35]

Medicinal fragrance balls seem to be used throughout Europe. Period examples, mentioned in personal inventory lists, as well as what are probably examples from paintings are available from France, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, England, and Spain.[36] Though metal pomander cases were used eventually in England, “aromatic material was originally sewn into linen bags or carried in silver or gold pierced containers known as “pouncet boxes.”[37]

Conclusion

Truly, this paper is merely scratching the surface. There are so many more avenues to explore, including: the perceived importance to Christians of the intercession of Saints and the divine in healing, the effects of the crusades on cultural exchange with the East, the use of pomanders by Jewish communities and the Muslim world, pomanders’ relationship with older and persistent folk healing traditions, how did experiencing the Black Death change peoples’ world view and relationship with medicine … and so much more. But hopefully, these words will help give us a more rich understanding of the pomander as a healing form used by a people who relied heavily on symbolism and associations in a world that was very different from the one we inhabit in the modern West, and inspire further research. To learn how to craft a pomander yourself, please visit my blog where I include details and instructions. A list of links containing images of pomanders are also included.

————–

End Notes

[1]Mortimer, Ian, page 7.

[2] Freedman, Paul, page 81.

[3] Mortimer, Ian, page 190.

[4] Sterner, Carl S.

[5] Sterner, Carl S.

[6] Mortimer, Ian, page 190-1.

[7] Freedman, Paul, page 81.

[8] Launert, Edmund, page 20.

[9] Ibid, pages 20-1.

[10] Ibid, page 22.

[11] Ibid, page 23.

[12] Smith, Julia H. M., page 145

[13] Launert, Edmund, page 23.

[14] Ibid, page 81.

[15] Freedman, Paul, page 4-5.

[16] Ibid, page 81.

[17] Ibid, pages 4-5.

[18] Ibid, page 105.

[19] Ibid, page 108.

[20] Ibid, page 135.

[21] Ibid, page 119.

[22] Soden-Smith, R.H., pages 337-9.

[23] Launert, Edmund, pages 18.

[24] Soden-Smith, R.H., page 340-3.

[25] Wartski

[26] Ibid, page 22.

[27] Cavendish, George, page 25.

[28] Launert, Edmund, page 17.

[29] Turner, T.H., pages 344-5.

[30] Dyett, Linda

[31] Launert, Edmund, page 21.

[32] Freedman, Paul, page 68-9.

[33] Launert, Edmund, page 18.

[34] Freedman, Paul, page 68-9.

[35] Launert, Edmund, page 24.

[36] Larsdatter

[37] Launert, Edmund, page 17

Bibliography

Beveridge, William. Thesaurus Theologicus: or a Complete System of Divinity: Summed Up In Brief Notes Upon Select Places of the Old and New Testament. Oxford, W. Baxter, 1710. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/thesaurustheolog00beve. Accessed 22 June 2018.

Boeser, Knut. The elixirs of Nostradamus: Nostradamus’ original recipes for elixirs, scented water, beauty potions, and sweetmeats. Moyer Bell, 1996.

Cavendish, George. The Life and Death of Cardinal Wolsey. 1641 (Written before 1562). Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/TheLifeAndDeathOfCardinalWosley. Accessed 9 July 2018.

Dyett, Linda. “Small Wonders – Aromatic Adornments.” Ganoksin, 2003, https://www.ganoksin.com/article/small-wonders-aromatic-adornments/.

Encyclopaedia Britanica – Ambergris. “Ambergris.” Encyclopaedia Britanica, https://www.britannica.com/science/ambergris. Accessed 20 June 2019.

Freedman, Paul. Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2008.

Larsdatter. “Pomanders.” Medieval and Renaissance Culture, Larsdatter, www.larsdatter.com/pomanders.htm. Accessed 23 June 2018.

Launert, Edmund. Perfume and Pomanders: Scent and Scent Bottles through the Ages. Potterton Books Ltd., 1987.

López-Sampson, Arlene, and Tony Page. “History of Use and Trade of Agarwood.” https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs12231-018-9408-4.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2018.

Mortimer, Ian. The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England. London, Vintage Books, 2009.

Nunn-Weinberg, Danielle. “The Painted Face: Cosmetics during the SCA Period.” Elizabethan Costume, http://www.elizabethancostume.net/paintedface/. Accessed 23 June 2018.

Smith, Julia H. M. “Portable Christianity: Relics in the Medieval West (c. 700-1200).” 2010 Raleigh Lecture on History, https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/1953/pba181p143.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2018.

Smollich, R. Der Bisamapfel in Kunst and Wissenchaft. Stuttgard, 1983.

Soden-Smith, R. H. “Notes on Pomanders.” The Archaeological Journal; Published Under the Direction of the Central Committee of the Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland for the Encouragement and Prosecution of Research Into the Arts and Monuments of the Early and Middle Ages, vol. 31, 1874, pp. 337-9, https://archive.org/details/archaeologicaljo31brit. Accessed 21 June 2018.

Sterner, Carl S. “A Brief History of Miasmic Theory.” August 2007, http://www.carlsterner.com/research/files/History_of_Miasmic_Theory_2007.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2018.

Turner, T. H. “The Will of Humphrey de Bohyn, Earl of Hereford and Essex, with Extracts from the Inventory of his Effects, A.D. 1319-1322.” The Archaeological Journal; Published Under the Direction of the Central Committee of the Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland for the Encouragement and Prosecution of Research Into the Arts and Monuments of the Early and Middle Ages, vol. 2, 1844, pp. 344-5. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/archaeologicaljo02brit. Accessed 22 June 2018.

Twomey, Lesley K. “Perfumes and perfume-making in the Celestina” The Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, Volume 86, Number 1, 2009, Liverpool University Press. Internet Archive, http://muse.jhu.edu/article/259087 Accessed June 21, 2018.

Wartski. “Pomander, German, 16th Century.” Wartski, http://www.wartski.com/collection/a-silver-gilt-pomander/. Accessed 23 June 2018.

Wikipedia – Pomander. “Pomanders.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pomander. Accessed 20 June 2018.

Zajaczkowa, Jadwiga. “Scents of the Middle Ages: Uses of the Aromas of Herbs, Spices and Resins.” http://www.gallowglass.org/jadwiga/herbs/scents.html. Accessed 19 June 2018.

One comment

Comments are closed.