Arts & Sciences Research Paper #18: Early Quilting and Patchwork: A Short Introduction

Our eighteenth A&S Research Paper comes to us from Mistress Sarah Davies of the Barony of Bergental, who introduces us to the surprising world of historical quilting, where we discover some familiar friends and some quite unfamiliar new ones! (Prospective future contributors, please check out our original Call for Papers.)

Early Quilting and Patchwork: A Short Introduction

The word “quilt” summons a host of images:

- Thrifty pioneer housewives cutting up worn clothing to piece elaborate patchworks for their families.

- Album quilts raffled off for a worthy cause.

- Wholecloth petticoats worn by colonial dames who danced with George Washington, then carefully preserved in a museum.

- Brightly colored feed sack quilts during the Depression.

- Community quilts telling the story of a town from its founding to the Bicentennial.

- Inexpensive versions of patchwork quilts sold in department stores for families wanting that “country look” in the bedroom.

- Cherished art quilts hanging in museums or going for high prices at auction.

The popular image of the quilt is of the quilt is modern, calico, and as all-American as an apple pie. If the word “medieval” ever comes up, it’s because someone made a Game of Thrones quilt with appliqued dire wolves in the border.

The problem with this familiar stereotype is thatit doesn’t begin to reflect reality. Patchwork and applique may be most associated the United States, but quilts themselves are anything but modern. Quilted carpets were prized on the steppes of Central Asia, quilted garments padded Crusader mail and protected Elizabethan fencers, quilted coverlets graced Tudor bed chambers, and quilted heraldic tapestries hung in Hungarian throne rooms. The evidence is scattered and sometimes hard to recognize, but quilting and patchwork were hardly alien to medieval Europe.

Contents

Definitions

Origins

The Earliest European Examples

Quilted Armor

Domestic Quilting and Patchwork

A Cloth of Honor and a Pillow

Later Developments

Henry VIII: Quilt Owner

SCA Uses

Further Reading

Where to Examine Historical Quilting Firsthand

“Quilt” and “patchwork” are so strongly associated that most people think that a quilt must be patchwork, and a patchwork must be a quilt. Not only is this not true, it confuses two very different types of needlework. A more accurate description would be as follows:

- Quilting is a type of padded embroidery that takes two layers of fabric sandwiched with padding of some sort, then stitched together in a decorative pattern. The word derives from the Latin culcita, a padded mattress similar to a modern futon. Equivalents in European languages include coltra (Italian), colcha (Spanish and Portuguese), coite (French, later superseded by courtepointe), and culte (the Netherlands).

- Patchwork or piecing is a type of sewing that takes several different types and colors of cloth, cuts them into geometric pieces, and stitches them back together in a decorative. Most are lined to protect the seams, but they do not need to be padded or quilted.

- Patchwork quilts are quilted bedcovers consisting of a pieced upper layer, an inner padding, and a plain backing held together by geometric or decorative stitching.

Most early quilts were whole cloth (non-pieced), usually of fine linen or imported silk. The first tantalizing hints of what might be medieval patchwork date from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, with one surviving artifact that might have been both pieced and quilted. Even then, it’s not at all clear that this item was intended for a bed, as evidence suggests it was more likely intended as a cloth of honor for a royal throne room.

The first known quilted object is a quilted linen carpet dating from around the first century of the Common Era. It was found in a Siberian cave tomb, and the central motifs (primarily animals, with abstract spirals on the borders) are wool appliques stitched into place with couched cording on the raw edges, while the background is diamond quilted in a coarse running stitch.

Whether the Siberians developed quilting on their own or learned it from outsiders, its advantages in such a cold climate are obvious: warmth without bulk, strength without stiffness, and easily adapted to multiple uses. It was also unusual enough that it could be traded for luxury goods along the Silk Road and other trade routes running across Central Asia down to the Mediterranean trade ports.

This seems to be exactly what happened. The next known quilted objects were both trade goods, and were both found in archaeological digs. One, a quilted slipper that seems to have been cut down from a larger object (a bed quilt or carpet), was actually found in a rubbish tip along the Silk Road. It was likely made around the eighth or ninth centuries CE, and is a very typical “Turkish slipper” with a low vamp and tilted toe. It is of linen padded with cotton or linen tow, backed with more linen, and quilted in the backstitch with coarse linen thread. It was almost certainly intended for indoor wear, as the sole is made from the same quilted item as the rest of the slipper.

The other early quilted object, a quilted wool funeral pall dating from the fifth or sixth centuries, is more problematic. It was found in a Merovingian tomb in the 1990’s, and unlike the slipper, it seems to have been made in Europe, or at least for the European market; it is of wool, not linen, and is quilted with cotton thread and stuffed with cotton thread, both imported from Egypt. Without further examples, we can only speculate as to its origins, but the pall’s existence, and the use of expensive imported materials in its construction, suggests that there might have been a quilting industry, at least on a small scale, either somewhere in the Mediterranean Basin or perhaps in Merovingian France itself. Without further examples, we can only speculate.

The Earliest European Examples

Unfortunately, there is almost no evidence of quilting anywhere near the West for the next several hundred years. There are a handful of references in tax records to silk quilts being sent by the bale to local rulers, but these are exclusively Asian. There is only one written reference to a quilt in a European record and one painting showing what might be a pieced or quilted item, with no physical evidence until the early fourteenth century.

The written reference is a French poem from the 12th century, La Lai del Desire. This little chivalric romance, only a few hundred lines long, includes a description of a bridal bed covered with a “quilt of two sorts of silk cloth in a checkboard pattern, well made and rich: “Sur un bon lit s’ert apulé / La coilte fu a eschekers / De deus pailles ben fais e chers”. (Lais inédits des XIIe et XIIIe siècles, ed. Francoise Michel, Paris, 1836: 18-19.) The word coite is used so casually that it’s clear that the author simply assumed that his audience, wealthy, sophisticated, and used to the very best, would not need to be told what a coite was, or how it was made.

The painting, by the school of the Italian artist Cimabue, is more intriguing. Dating from around 1275-1300, this small, elegant panel painting shows the Madonna and Child seated on a low couch, flanked by Saints Peter and John the Baptist while two sweet-faced angels hold up a piece of fabric behind the Madonna as a sort of floating cloth of honor. The cloth of honor, which is so strikingly different from the usual brocade or cloth of gold seen in such paintings, was hailed by art historian Roberto Longhi as a “stupendous, decorative invention,” and it’s not hard to see why. Black and white gyronny patterns alternate with blocks of red in what is almost certainly an attempt at showing a patchwork cloth of alternating red brocade and black and white pinwheels. Whether this cloth was actually quilted is not clear, as the greenish highlights on the red are probably intended to depict a brocade pattern and not stitching. However, it’s very clear that something that we’d call a patchwork quilt was not out of the question in the SCA period.

As tempting as it is to conclude that the little Cimabue painting indicates a thriving patchwork and/or quilting industry in the late thirteenth century, however, there is still no definitive evidence for this. Spanish silk weavers, steeped in the Moorish decorative tradition of geometric patterns, produced magnificent brocades that bear such a strong resemblance to patchwork that least one quilt historian assumed that a brocade cope from the 1200’s was patchwork. The same may well apply to a mid-fourteenth century fresco by Florentine artist Taddeo Gaddi of The Marriage of the Virgin. This homely scene, which includes a groomsman giving St. Joseph a congratulatory slap on the back, shows a geometric textile of red, green, orange and white hanging from a roof…and though it certainly looks like a quilt, and could easily be a quilt, it could just as easily be a piece of Spanish brocade.

Fortunately for historians and SCAdians alike, more definite evidence for both quilting and patchwork begins to appear around the year 1300. Professional armors specializing in quilted gambesons and other forms of padded armor begin to crop up in court records. The French court had a “courtepointier,” or quiltmaker, while a few decades later someone known only as “Niccolo de la Coltra” worked in Padua as ‘the master of quilts.” These professional quiltmakers were far from unique; professional quilt and quilted armor guilds were active in Bologna, Rome, Florence, Venice, and Genoa by the fourteenth century, often in association with cotton guilds. Southern France was another center of the European quilting industry, particularly whole cloth white quilts.

The primary product of these quilted armorers were closely fitted padded armor intended to be worn on the upper body, either over or in place of steel armor. They were known as jacks, arming doublets, coat armor, jupons, aketons, or haketons depending on area and period, and their construction was strictly regulated. One Italian guild required that jupons be padded with linen or cotton tow to the depth of three fingers’ breadths on the shoulders and two fingers’ breadths upon the torso for maximum protection. Aristocratic versions were often made of rich fabrics such as heavy velvets or silk brocades, then padded so heavily in the chest that their wearers were compared to greyhounds. Less exalted versions, made of linen padded with cotton or wool, were lighter, cheaper alternatives to metal armor, so they became a popular option for foot soldiers, sappers, or archers. There were even jacks where small steel plates were sewn inside the padding, then layered with more cushioning for extra protection.

Several such pieces have survived, most in surprisingly good condition. The most famous include the “Black Prince’s jupon” in Canterbury Cathedral, the coat armor of Charles VI in Chartres, the doublet of Charles de Blois in Lyon, and a curious German tunic that layers linen, padding, and small steel rings for extra protection. Less famous but arguably more interesting is the Rothwell Jack, a rare piece of armor worn by a common foot soldier or archer. Unlike its aristocratic kin, the Rothwell Jack is so crudely made that it was probably thrown together on short notice, either by a sailmaker or possibly its original owner. Its materials, over twenty layers of raw wool and coarse linen stitched together heavy linen thread, are equally humble, and again indicate that it was made by a non-professional. Although local historians long claimed that the Jack belonged to John of Gaunt, it almost certainly belonged to one of his archers, as the right armscye is all but worn away while the left is largely intact.

Quilted armor disappeared late in the SCA period thanks to the invention of firearms, as quilted armor was useless against a bullet or other small projectile. However, protective garments of quilted linen were still popular among court tennis players, as in a 16th century painting by Francesco Becaruzzi, while quilted doublets of leather lined with silk were used as fencing jackets by the wealthy.

There is also an abundance of artistic evidence for quilted clothing and armor during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The best known is Hans Memling’s The Chasse of St. Ursula, but there are several funerary sculptures, particularly in Germany and Switzerland, showing knights wearing quilted gambesons or jacks. There is also a tiny Italian ivory of The Flight into Egypt showing St. Joseph wearing a quilted tunic that might have begun as coat armor, although it equally could show a peasant tunic quilted for warmth.

Domestic Quilting and Patchwork

There is less somewhat less physical evidence for domestic quilting during the early Middle Ages, while aside from La Lai del Desir, there is nothing in writing about patchwork until a French memoir of 1507. However, there are a handful of extant quilts and two pieces of patchwork that hint at a much richer tradition that has been lost to war, wear, and time.

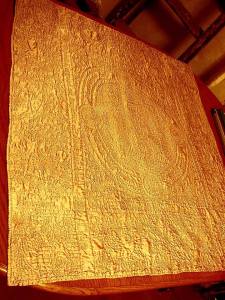

The oldest known actual whole cloth European quilts are three trapunto, or stuffed quilts from Italy. Two, the so-called Guicciardini quilts, were probably made for a Florentine wedding in the 1390’s (and may have originally been a wallhanging), while a third seems to have been an actual coverlet. All are made with the same materials (linen top and back, cotton padding, linen thread) and with the same technique (dark brown backstitched outlines on the decorative motifs, running stitch on the backgrounds). The iconography and the motifs are so similar that these items were all but certainly made in the same workshop, while the designs and the captions on the Guicciardini quilts are in an otherwise rare Sicilian dialect.

The Guicciardini quilts, one in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, one in the Museo di Bargello in Florence, have been the subject of scholarly controversy for nearly a century. They seem to have been made for a wedding between two powerful Florentine families around 1394, but whether they were originally a set of two quilts for two beds, one quilt for an enormous ceremonial bed, or a huge wallhanging is not known. Some scholars, notably Arthurian specialist R.S. Loomis and quilt historian Susan Young, believe they were designed as a set, but recent analysis by Sarah Randles indicates that they were probably one huge piece that was cut apart and reassembled into two quilts for reasons that made sense at the time. The piece in the Bargello belonged to Guicciardini descendants as late as the 1920’s, while the section in the Victoria & Albert was acquired around the turn of the twentieth century. The iconography, a Sicilian retelling of the story of Tristan and Isolde depicted in large squares similar to the panels on a modern comic book, seems strangely inappropriate for a wedding gift, especially if the quilt(s) was indeed intended for use on the bridal bed.

Less well known is the third quilt, which was owned by the Pianetti family. This piece, only half of which was extant when it was last photographed, once again showed Tristan and Isolde, only in central medallion surrounded by heavily stuffed fleur-de-lis. The border shows allegorical figures feasting in vineyards and gardens, but there are no captions so the meaning is not clear. It was last seen in 1938 and has vanished without a trace, leading to the tragic but unavoidable conclusion that it might have been lost during the massive destruction of World War II a few years later.

Quilt historians assumed for decades that the Guicciardini and Pianetti quilts were the only surviving medieval quilts. However, a startling discovery around 2000 in Budapest challenges this assumption. Archaeologists excavating the old Tekeli Palace found a silk textile depicting the arms of the Arpad and Angevin dynasties encased in mud at the bottom of a rubbish shaft. The Anjou Textile, as it is now known, was wet-cleaned and disinfected by conservators to remove mud and bacteria, then examined for clues to its construction and original purpose. The mudball had been found alongside coins dating between 1390 and 1427, while physical analysis of the actual cloth indicated that it was at least a few decades older than the coins.

Close examination revealed that this textile was pieced and appliqued in red, white, blue, and golden silk, while its age indicated that it was likely made not long after the Cimabue painting with the patchwork cloth of honor. Stitch patterns on the cloth and a few bits of cotton padding and linen thread clinging to the wrong side clearly indicated that the Anjou Textile had originally been quilted in a diamond pattern at least twenty or thirty years before the Sicilian whole cloth quilts.

Most striking of all, Hungarian court records from the reign of King Charles Robert reference a large order of red, white, and blue silk from Italy, while the king’s Great Seal of 1331 clearly shows a patchwork cloth of honor that is all but identical to the Anjou Textile. As unlikely as it may seem, the evidence indicates that there is a strong possibility that the Anjou Textile was pieced and quilted no later than 1331, and probably about ten years earlier.

As important as the Anjou Textile, it is not the most elaborate piece of early patchwork. That honor must go to the Impruneta Cushion, one of the most remarkable surviving pieces of early needlework, regardless of technique.

This small pillow, only one foot square, was found in an Italian tomb in 1947. The little town of Impruneta, about fifteen kilometers south of Florence, had been bombed in 1944 during the Allied advance up the Italian peninsula. It wasn’t until 1947 that the town had the money to check on the tomb of its fifteenth century bishop, Antonio degli Agli, which had been knocked open when bombs struck the pilgrimage church of Santa Maria dell’Impruneta.

Bishop Agli himself had suffered little damage during the attack, but the most significant find in his tomb was the tiny cushion that had been placed under his head by his grieving niece, Deinara, when he died in 1477. The cushion, which seems to have been one of the bishop’s favorite possessions, turned out to be not a simple pillow but a dazzling piece of early patchwork, with elaborate star and checkerboard patterns on the front and a simple but striking geometric pattern on the back.

Analysis by an early conservator known only as “Signor Clignon,” supplemented by a thorough conservation/stabilization by the Tuscan state conservation agency in 1990, revealed that no fewer than thirty different types of silk lampas, brocade, damask, satin, and velvet were used to piece the front of the cushion. The actual pieces ranged in size from approximately 1.5 inches to perhaps a quarter inch square, and were so finely and accurately stitched that conservators speculated the makers used stiff paper or pasteboard to stabilize the shapes during construction. The seams, which had been repaired at some point during Bishop Agli’s lifetime, were all reinforced with couched cording. The back of the cushion was pieced of inch square pieces of wool arranged in concentric squares. This not only produced a noticeable sense of movement, but is all but identical to the modern patchwork pattern known as Trip Around the World. Just as on the front, the seams on the back were reinforced with couched cording.

Italian scholars believe that the cushion was made between 1425 and 1455, as it was clearly used before being put in Bishop Agli’s tomb. As carbon dating would require destroying a large section of the cushion itself, it is not possible to give a more precise date unless Agli family records surface mentioning the cushion.

The Renaissance brought increased trade with the Eastern countries where quilting originated. The Ottoman Empire had a native tradition of quilted bedcovers and caftans; surviving examples from the courts of 16th and 17th century sovereigns such as Suleiman the Magnificent and Selim the Grim are worked in the running stitch on silk broadcloth and brocade, lined with cotton to get around the Qu’ranic prohibition against silk garments. Court etiquette dictated that clothing be presented to foreign ambassadors, so it is possible that European diplomats posted to Constantinople returned with quilted caftans in their baggage.

This was the time when European countries established colonies and trading posts in Asia. India had a strong native quilting tradition and quickly began producing export work in cotton and silk (the very word calico, later the name of the favorite quilting cotton, is derived from Calcutta). Portugal in particular imported “pintadoe quilts” from its Indian possessions, as well as palampores and unquilted spreads that were later worked up into “colchas” on the Iberian peninsula. Several of these Indian/Bengali quilts have survived, including one in the collection of Hardwick Hall in England, almost a dozen in the Museum of Antique Arts in Lisbon, and a half-circle cape in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By the sixteenth century, silk and linen quilts were quite popular in wealthy households throughout Europe. Among the best examples of this is the 1547 death inventory of England monarch Henry VIII.

Henry VIII’s inventory provides a unique look at quilts in aristocratic households. He owned over one hundred quilts and quilted coverlets, including two quilts assigned to his bath, sixty “holland” quilts of fine linen for bedding, and approximately forty quilts of various types of silk. One of the quilts, a green sarcenet coverlet worked in roses, pomegranates, and fleurs-de-lis, may have dated from early in Henry’s marriage to his first queen, Catherine of Aragon, or even been part of her trousseau when she married his brother Arthur. Other quilts were “payned” (pieced) in color combinations such as purple and white, green and white, and five or six colors such as tawny, green, yellow, blue, crimson, and white. There were even two “quiltes of canvase to cover cartes,” presumably part of the equipment used to move the royal household on Henry’s frequent progresses.

Many of these quilts likely either Indian imports or European copies of expensive Indo-Portuguese work, such as the Indo-Portuguese silk quilts, but the “holland” quilts of fine linen stuffed with wool were likely made in Northern Europe. Four or five of these would be used as actual bedclothes, while a silk quilt, often very elaborately worked with metal or silk threads, would be used as a bedspread.

There are several uses for quilts and quilted objects in the SCA. The most obvious, and common, is armor. Although quilting was used for both gambesons and jacks, padded linen jacks cannot be made list legal. However, a finely quilted jack would look spectacular in court. A better choice for a heavy weapons fighter would be a gambeson or a quilted tunic worn over armor in cold weather. The only caution would be to use only cotton batts – synthetic batts do not breathe, and armor made from them could cause a fighter to overheat and suffer a heat stroke. Most pre-quilted fabric is made with polyester batts and should be avoided for this reason.

Another good choice would be quilted bedding, either pillows or bed quilts. Most fabric stores offer basic quilting classes, by either hand or machine. Machine quilting is obviously not period, but it’s possible to quilt a whole quilt in a day by machine. Virtually all modern quilts are made of cotton broadcloth or calico – again, not period, but washable, cheap, and very practical for camping. And Indian bedspreads are so close to palampores that a quilted version would make a fine addition to any campsite.

One warning: quilting is addictive. The calicos used for modern quilting are among the most beautiful cottons being made today, and who can resist beautiful fabrics? So don’t be surprised if what begins as a single gambeson, or a way to use up scraps, turns into a full blown obsession!

Colby, Averil. Quilting. HarperCollins, 1972.

Evans, Lisa. ‘”The Same Counterpoincte Beinge Olde and Worene’: The Mystery of Henry VIII ‘s Green Quilt”, in Medieval Clothing and Textiles 4, Robin Netherton, Gale R. Owen-Crocker, eds. Boydell Press, 2008.

—. “Anomaly or Sole Survivor? The Impruneta Cushion and Early Italian ‘Patchwork'”, in Medieval Clothing and Textiles 8, Robin Netherton, Gale R. Owen-Crocker, eds. Boydell Press, 2012.

Von Gwinner, Schnuppe. The History of the Patchwork Quilt Origins: Traditions and Symbols of a Textile Art. Schiffer Publishing, 2007.

Where to Examine Historical Quilting Firsthand

Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia

Historic Deerfield in Massachusetts

International Quilt Study Center & Museum in Nebraska

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Shelburne Museum in Vermont

Victoria & Albert Museum in London