How To Prepare Documentation

The following article was written by Lady Ose Silverhair as part of the Gazette’s ongoing “How to…” series.

The following article was written by Lady Ose Silverhair as part of the Gazette’s ongoing “How to…” series.

Here in the East Kingdom we are lucky enough to have several events each year that celebrate the skills of our artisans and scientists. Are you thinking about participating in an Arts & Sciences event but are wary of those two words in the announcement “documentation required”? Here are a few tips on how to prepare.

The best advice I can give you is this: don’t wait until your project is done to write the documentation. This will only cause you stress. Keep notes about books and articles you’ve read, websites you’ve visited, museum exhibits you’ve seen, or people you’ve spoken with. It is much easier to write something down when it happens than to try to remember it later. Even if you never enter a display or competition, you will thank yourself later as you continue to explore your chosen field.

Are you trying to recreate a period recipe, dance, or pigment? Keep track of your trials and errors. Experimentation is full of mistakes. It is how we learn. Use your documentation as a way to describe your process. Let someone else read your documentation before the day of the event. It’s a great way to be sure your explanations are clear and complete.

Finally, it’s time to prepare for the event. Like any good story, there are six questions you should consider as you put your documentation together.

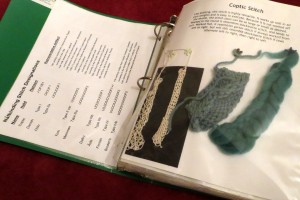

What is your project? Is there a particular period piece that was your inspiration? Include a photo. Where is it from? When does it date from? How was the piece made in period?

You’ve chosen an approach for your project. Why did you make the choices you made? Did you recreate it with period methods and materials? What challenges did this pose? If you made a change or substitution, be sure to explain why. Are you using a period technique to create a unique item rather than a reproduction? Explain how you went about it. Show the judges your critical thinking processes and how you are putting your research into practice.

Lastly, who are the sources for your information? Did you base your project on a particular artifact that you saw in a museum? Did you reference a period source from a library? Did you read a book that gives directions for the technique you used, or one that describes the qualities of similar period pieces? Including a bibliography helps the judges understand the basis of your knowledge.

And don’t forget that other who – you! Unless the competition rules say that it will be blind judging, always put your name on your documentation. People want to know who you are.

Sometimes we are interested in something where period sources do not exist. An artifact verifies that something was done in period, but we have no record of how it was done. The only way to understand the artifact is to experiment. This is in the best medieval and renaissance tradition of scientific experimentation to understand the world. In this case your documentation should clearly describe your experimental process. What is your hypothesis? What question are you trying to answer? What technique or item are you trying to reproduce? What method did you use to test your hypothesis or answer your question? What were the results? Were you successful? If not, how did you modify your method to improve on the results? Can you repeat the test and get the same results? What did you learn? Photos can be very useful. Also consider separating any data tables from your descriptive documentation when that makes it easier for people to understand your process.

When possible, keep your documentation concise. Two to four pages are often enough to get your important points across. Judges will have many projects to review that day. If you feel your documentation needs to be longer, include a summary at the beginning, or consider submitting a research paper. Remember that you may know more than your judges. While the event organizers will make every effort to have judges who know about your interest, it isn’t always possible. Don’t leave something out because you think “everyone” knows it. They may not. Consider your documentation as the jumping off point for a conversation about this thing that inspires you. Share your enthusiasm!

Can this article (and/or others) be reproduced in other lists, in part or in it’s entirety. Full credit will be given.

I’m delighted that you find this information helpful. Please feel free to reproduce it, or other articles from the site, as long as credit is given. — Lady Ose

I am brand new to the SCA and have found this article very helpful. Countess Fortune St Keyne was kind enough to direct me to this article. Thank you