A&S Research Paper 36: Medieval and Renaissance Banking

Medieval and Renaissance Banking Or “How to Succeed in Business Without Getting Condemned for Usury”

Lord Richard Heyworth: https://wiki.eastkingdom.org/wiki/Richard_Heyworth

The Moneylender and his Wife (1514)

Continue reading “A&S Research Paper 36: Medieval and Renaissance Banking”

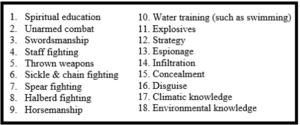

Those selected as field agents trained in the eighteen skills listed in the box to the right (Masaaki, 2004, p. 22). These skills provided the ninja a wide range of abilities ranging from spying or scouting to assassination and battlefield combat.

Those selected as field agents trained in the eighteen skills listed in the box to the right (Masaaki, 2004, p. 22). These skills provided the ninja a wide range of abilities ranging from spying or scouting to assassination and battlefield combat.