Arts & Sciences Research Paper #22: Recreating an Illuminated Persian Manuscript Page

Our twenty-second A&S Research Paper comes to us from Lady Onóra ingheainn Uí Rauirc of the Barony of An Dubhaigeainn. She takes us through her process of recreating a manuscript page in the Persian style, and shows us some fascinating things in the process. (Prospective future contributors, please check out our original Call for Papers.)

Recreating an Illuminated Persian Manuscript Page

Table of Contents

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Conclusion

Examples of Historical Pages

Reference

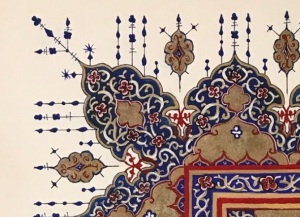

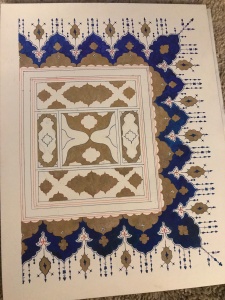

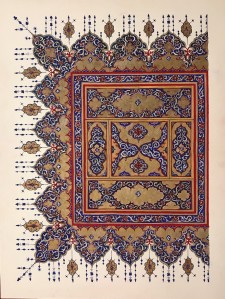

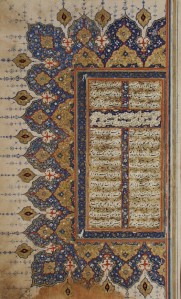

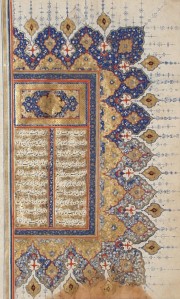

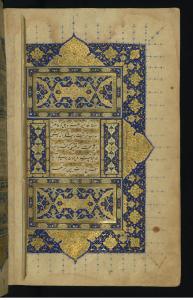

I set out to create a double page illumination inspired by Persian manuscripts painted during the Safavid Dynasty; this article describes the process for the left-hand page, which is all illumination. Although the Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1736 in what is present day Iran, I chose an art style that was popular with scribes in the beginning of the dynasty, specifically between 1527 and 1550 (see figures 1-4). During this time, the designs were simpler in comparison with those found in the later Safavid period. The floral vine work and geometric patterns were much less complex, and scribes used fewer shades of pigments.

I was inspired to create this piece while researching Mongolian culture. I came across several sources that described the Mongol influence on Persian art after they invaded the Persian Empire in the early 13th century. I began to dig further into the illuminated manuscripts created by Persian scribes after that invasion and was inspired to challenge myself with a style of art which is completely new to me.

[Back to top]

| Historical Materials Used | Materials I Used |

| Polished cotton, hemp or flaxseed paper | Heavy cotton hot pressed paper |

| Charred twig | Graphite pencil |

| Mineral pigments in a gum Arabic base | Gouache pigments in a gum Arabic base |

| Squirrel fur brushes with a feather handle | Nylon brushes |

| Gold leaf paint | Gold leaf paint |

Persian scribes were highly regarded for their art and chose only the finest materials to use for their manuscripts. They started with a high quality paper. On the western side of the Persian empire, now modern day Saudi Arabia, artists used a variety of fibers for their paper including flaxseed and hemp. However, artists on the eastern side of the empire near India used cotton fiber paper. Based on my research, I posit that the use of cotton fiber paper was probably adopted from Indian artists since cotton was the primary type of paper fiber used in Indian art (Barkeshli, 2009).

Historically, this scribal paper was created by soaking wet fiber in a sizing material such as starch, fish glue, vegetable glue or gum Arabic. The sizing material acted as a filler for the paper fibers and created a smooth waterproof surface. The scribe would prepare the paper for painting by burnishing the page to a glossy finish using a smooth agate stone. This created a slick, almost impermeable surface to work on. I used a high quality hot pressed watercolor paper for my piece. This paper is 100% cotton fiber sized with natural gelatin. It was prepared by applying heat at a high pressure to create an ultra smooth finish. This technique mimics the polishing process of period scribes. I chose this type of paper because the materials and the manufacturing technique used are the closest match to its’ period equivalent available.

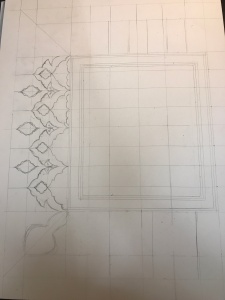

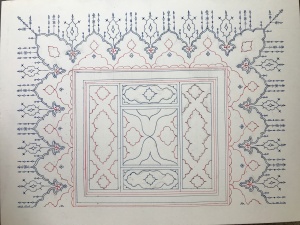

After the paper was prepared, the scribe would use a charred twig to sketch out a rough draft of their design onto a thin sheet of paper or animal skin. This was called the “tarh”. The sketch was then transferred to the final sheet of paper using the pounce method, which works the same as modern carbon paper. The pounce method involved filling a linen bag with charcoal powder and bouncing the bag on the underside of the tarh to apply a thin coat of charcoal dust to the back of the sketch. The draft was then placed over the prepared final paper. The artist carefully sketched over the design, pressing the charcoal powder onto the polished paper (Sardar, 2003). To sketch my design, I chose to use a fine graphite pencil. I felt that the fine tip of a mundane pencil would be easier to use since the intricate detail of this art is new to me. Instead of tracing the design, I started by using a straight edge to measure out the spacing and placement of the shapes I would use, then I sketched my design directly onto my final paper. Carefully placed guidelines eliminated my need for a rough first draft, which saved me a lot of time.

Persian artists began painting by laying down all the gold pigment first. This process was called “tazhib,” which literally translates to “gilding” and is a term still used today. Artists created gold paint by placing a thin sheet of gold into a porcelain bowl and adding a small amount of honey. This combination was thoroughly smashed with a porcelain mortar and pestle into a fine dust (Pakzad, 2016).

Warm water was then added in small amounts until the honey was dissolved. After the gold dust settled to the bottom of the bowl, the gold was carefully strained until the water was removed. The process of adding water, mixing and straining was repeated two or three times to clean the gold.

The artist then mixed in a binder such as gum arabic or isinglass (a glue obtained from fish bones), and set the paint to dry. Water would be added to rehydrate the gold for painting. For my piece, I followed this method as closely as possible to maintain period accuracy. Although I could not find documentation on the specific type of honey Persian artists used, I suspect that they used honey that was locally collected instead of honey that was imported from neighboring regions since beekeeping was serious business in the Persian Empire. In fact, the art of beekeeping in Persia was inspired by the Egyptian mastery of the craft. (Crane, 1995). With this thought in mind, I chose to use locally collected honey since it was readily available to me.

To finish the tazhib process, artists burnished the gold with a smooth agate stone. This is supposed to smooth the surface of the paint and create an illuminated effect. I attempted to use an agate stone to burnish the gold on my piece, however I found that it rubbed the paint off the paper so I skipped this step in the final product. I will certainly research this issue in more depth so I can use this technique on future scrolls.

Once the tazhib process was complete, the artist began to add color to the painting. Colored paints were made using mineral pigments mixed with a binder. To prepare colored paints, Persian artists crushed the stone or ore into a fine dust. The mineral was then cleaned by pouring water over the mineral, allowing to mineral to precipitate, pouring off the water and repeating. The mineral was then dried, and a small amount of gum Arabic was added as the binder for the pigment (Pakzad, 2016). According to several sources, gum arabic was the most popular binder; however, I also found instances where isinglass or egg yolk was used instead. Once the minerals were mixed with the binder, they were dried and rehydrated when needed (Pakzad, 2016; Arias, 2008).

The color palette I used was chosen to specifically match the colors used in early Safavid Dynasty manuscripts. The table below shows the most popular colors used and what they were derived from. I used wet gouache pigments mixed with gum arabic and a little water for my scroll. I chose gouache since it was the most readily available paint to me at the time. Upon close inspection of my reference pieces (Examples of Historical Pages), I noticed that the pigment was opaque and very evenly applied. I mixed a small amount of gum arabic and water with my paint to create the same visual effect while maintaining the use of period materials.

| Color | Origin |

| Azure | Azure stone |

| Vermillion | Cinnabar ore |

| Orpiment Yellow | Orpiment mineral |

| Malachite Green | Malachite stone |

| White Lead | White lead |

| Black | Carbon soot |

Of these colors, I used azure, vermillion, yellow, white and black as they matched my reference materials most closely (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Persian artists used fine brushes of squirrel fur to apply paint to their manuscript. According to the writings of Sadiqi Beg, a poet, biographer and well known artist of the Safavid period, the squirrel fur was trimmed and attached to a pigeon feather with silk thread (Barkeshli, 2009). I chose to paint my piece with synthetic nylon brushes instead. I felt that since this was my first time painting in this style, it would be beneficial to me to use a synthetic brush so I could maintain better control over the flow and precise application of the paint. I am looking forward to learning more about Persian brush making so I can make period brushes in the future.

This project was certainly a challenge, but I learned so much in the process. One thing that I found surprising was drawing the design was not as difficult as I thought it would be. Although Persian manuscripts look intimidating with their ornate and intricate designs, they are actually quite simple. Each design is composed of a repeating pattern and filled in with vine work. The pattern can be broken down into sections and simplified into basic shapes including circles, triangles and diamonds. I found that when I used this common artist technique of breaking things down into simple shapes and patterns it was pretty easy to draft the piece.

I did, however, run into challenges making the gold paint. I knew that I would have to be really diligent in grinding the gold leaf down to a fine dust, but I was not prepared for how difficult and tedious this process would be. This step alone took at least an hour of sheer muscle to grind eight sheets of gold leaf. I also needed to resort to grinding the gold with my bare fingers. Although the porcelain mortar and pestle I own is similar to those used in period, I could not seem to create a fine enough dust. I plan on researching this issue in depth to obtain better results in future paintings.

The second challenge I ran into with the gold was drying time. I learned that the dry environment that is characteristic of the Middle Eastern dessert is very important for the paint to dehydrate properly. Since it was very humid at the time, my paint took three full days to dry. Despite the trouble I went through, I truly think it was worth it to make the gold paint for this piece. I get a lot of joy out of learning a new period technique and it was exciting to be able to apply it to my own work.

In the future I plan on making the gum arabic for my next batch of paint using period techniques. The readymade gum arabic I used was quite watery, and I think it would be beneficial to be able to control the consistency and create a thicker medium when needed. I also noticed that mixing the gouache pigments with gum arabic and water resulted in a blotchy finish in my painting. My theory is that this is due to the inconsistency in the water to gum Arabic ratio in the paint. Handmade gum Arabic may fix this issue as well in the future.

I plan to continue to create Persian illuminated manuscripts in the future, since I most certainly enjoyed this project. For my next piece, I would love to work with a complete set of period mineral pigments. I also plan on making my own brushes. I absolutely loved the entire of process of researching and preparing this piece of illumination, and I look forward to continuing my research on Persian manuscripts.

Arias, Teresa Espejo et.al. “A Study About Colourants in the Arabic Manuscript Collection of the Sacromonte Abbey, Granada, Spain. A New Methodology for Chemical Analysis.” Restaurator: International Journal for the Preservation of Library and Archival Material, Vol. 29, issue 2 (2008)

Barkeshli, Mandana. “Historical and Scientific Analysis of Iranian Illuminated Manuscripts and Miniature Paintings.” Quarterly on the History of Iranian Art and Architecture vol. 5 issue 2 (2009) pp. 8-22

Crane, Eva. “Beekeeping in the Islamic World” Ahlan Wasahlan pp. 34-38 (1995)

Pakzad, Zahra. “Color Structure in the Persian Painting.” Review of European Studies vol. 9, issue 1 (2016)

Sardar, Marika. “The Arts of the Book in the Islamic World, 1600-1800.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (2003)