Arts & Sciences Research Paper #20: Knit Purses in 14thC Switzerland

Our twentieth A&S Research Paper comes to us from Lady Tola knitýr, of the Shire of Quintavia. She examines the history and background of these beautiful small purses, and then demonstrates how they can be made by a skilled modern craftsperson. (Prospective future contributors, please check out our original Call for Papers.)

Knit Purses in 14thC Switzerland

Table of Contents

I. Historical Overview of Knitting

II. Textiles and Religion

III. The Knit Purses of Sion and Chur

IV. Recreating a Sion-style purse

V. Conclusion

VI. References

I. Historical Overview of Knitting

The oldest items that can be truly defined as knit (rather than made with naalbinding techniques), are knitted cotton fragments from Egypt, approximately 11th to 12th Century. Slightly later, but still in Egypt, knit cotton socks appear, with museum authorities estimating that they were made somewhere from 1200-1500. These Egyptian pieces were the first knit in stockinette stitch in the round, where a tube is knit with needles that are pointed on both ends. In The History of Handknitting, Richard Rutt indicates that these were almost certainly knit with rods, that may have been hooked. Very few extant knitting needles have been found, which may be a result of the simplicity of double-pointed needles, but an excavation in York discovered two copper alloy rods with a rounded point on each end, dated to the late 14th century, that scholars suggest may have been used as knitting needles.

In Europe, the earliest knit pieces appeared in the mid to late 13th century, as a Spanish glove, Spanish cushion covers, and a mitten fragment from Estonia. Following these pieces are five knitted purses from Sion, Switzerland and a sixth purse found in Chur, in the German-speaking eastern Switzerland. All six are dated to the 14th century. The purses were all knit with silk thread, very finely knitted from the top down, closed at the bottom with a three-needle bind-off, and usually used two colors at a time to create a pattern.

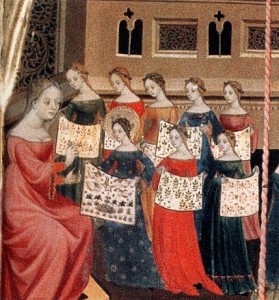

A number of paintings in the middle ages show Mary, mother of Jesus, knitting with double pointed needles. The “knitting Madonnas” lead me to believe that at this time, knitting was done by women in the home, rather than in guilds, as was the case towards the end of the Middle Ages.

Across Europe, the Roman Catholic church was a vital part of life in the Middle Ages. The papal states in Italy were the seat of power, and became independent from the Holy Roman Empire, which allowed the church to hold land as a sovereign entity. Massive landholdings as well as financial gifts to the church in the form of tithing helped the church become powerful politically. Because of the great importance and wealth of the church, the finest materials were used in furnishing churches and clothing the clergy. Precious metals like gold and silver, as well as luxurious silk, ivory, and gems, were crafted into decorations, vestments, and reliquaries used to hold the remains of holy places, saints, or items they had touched. Because of the importance of the church to this day, many textiles in the form of garments and reliquaries were preserved through the ages.

Many of these textiles were created by women, both nuns and laywomen, to show their piety and devotion to the church. Because of the importance of the textiles, which were largely in the form of intricate embroidered items, the Church kept detailed records of many of these donations. In some cases, it is unclear as to whether the names of the women who donated the textile items were the artisans, or commissioned the pieces for the church. Many Queens, such as Queen Matilda, wife of William the Conqueror, are listed as the donors of embroidered items. Queen Margaret of Scotland even established a workshop for noble women to gather and create religious textiles. While embroidery gets most of the attention in historical study and recreation, a number of church textiles were also knitted items.

III. The knit purses of Sion and Chur

The city of Sion is home to the oldest Roman Catholic diocese in Switzerland. Historical records reflect bishops there as early as the 4th Century. Several churches have stood in Sion over the centuries, and construction on the present-day cathedral began in 1450.

In the early 20th Century, Ernst Alfred Stückelberg was granted access to relics in the treasury of the cathedral of Sion. Stückelberg was a professor of Christian antiquarian studies at the University of Basel as well as a researcher and lecturer of Christian archaeology and monuments. Stückelberg’s essays do not detail the excavation of the artifacts, which could provide greater context for the items, but we do know that one of the items that he found was a wooden chest studded with gold-plated silver, which contained five knitted purses. During the Middle Ages, purses were used for both secular and religious purposes. The Sion purses are thought to have been used as reliquary bags, to hold the remains of saints.

The Sion purses appear in Richard Rutt’s A History of Handknitting, but were first studied by Brigitta Schmedding in Mittelalterliche Textilien in Kirchen Und Klöstern Der Schweiz (Medieval Textiles in Churches and Monasteries of Switzerland). Schmedding had a doctorate from the University of Freiburg, having written her dissertation on the Romanesque Madonnas of Switzerland in the 12th and 13th century, and also graduated from the Abegg Foundation’s three-year training in textile preservation. The purses are currently located in the Château de Valère, the historical museum in Sion. I have attempted to contact the staff of the museum to obtain color pictures of the purses, but have not received any response.

Schmedding also studied a sixth purse, found in Chur, Switzerland, which is generally referred to as the Chur purse and is strikingly similar to the Sion purses. Both Schmedding and Rutt conclude that the purses likely came from the same creator or workshop due to the similarities. I believe that these purses were likely knit by one woman, who then gave them to the church, since they are very similar and could represent devotion to the church.

The purses were all knit with silk thread, very finely knitted from the top down, closed at the bottom with a three-needle bind-off, and usually used two colors at a time to create a pattern. Schmedding indicates that the threads are s-spun (spun in a clockwise manner), but does not indicate whether they were singles or plied. Silk thread from the same time period used in embroidery and sewing was 2-ply, with the single threads Z-spun and the two threads plied together with an S-spin.

For the technique, Schmedding describes the knit in the round technique, describes the bottom of the purse being laid flat and knit together, and indicates that it was probably knit on a frame. Her description of the bottom of the purse matches the technique of a three-needle bind off, which is a technique used to join two pieces of knitting that are still on the needles, essentially binding off the stitches and seaming them together at the same time. With regard to Schmedding’s suggestion of a frame, the stocking knitting frame was not invented until 1589. There are, however, images of double-pointed knitting needles in art from the Middle Ages, as referenced earlier, so I would conclude that these purses were likely knit on double-pointed knitting needles.

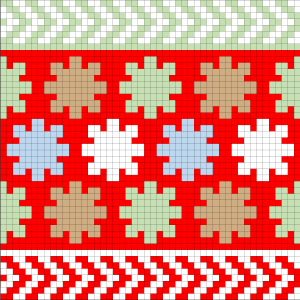

The following analysis relies mostly on Schmedding, but also references Rutt. Since Rutt’s names for the bags are simpler, each bag is referenced first with Rutt’s naming convention, then Schmedding’s, with the associated catalog number. I also created my own charts, because I found that I was not satisfied with Rutt’s interpretations (and Schmedding doesn’t have any charts). Rutt’s charts can serve as a starting point, but close examination of photos often reveals mistakes or omissions. There is even a case where he indicates different colors on a purse than Schmedding describes, and as Schmedding had documented hands-on experience restoring the purses, I am inclined to trust her conclusions over his. All photos are taken from Mittelalterliche Textilien in Kirchen Und Klöstern Der Schweiz: Katalog; the charts that follow each description are my own.

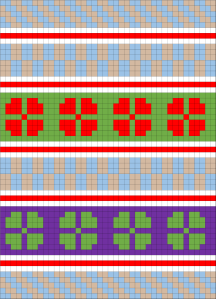

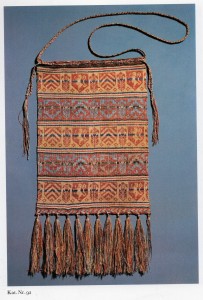

Sion relic-purse I (268 Reliquary bag), p. 285

Measurements: Bag is 27 cm x 24 cm (10.6” x 9.4”) Fringe is 17 cm (6.7”) Pattern repeat is 2.7 cm x 1.6 cm (1.1” x 0.6”)

Gauge: 70 stitches and 70 rows = 10 cm (4”) (a note about gauge – knitting gauge is measured by the number of stitches and the number of rows in a 10 cm x 10 cm or 4” x 4” square)

Colors: Red, light green, light blue, white, beige

Sion relic-purse II (271 Reliquary bag), p. 287

Sion relic-purse II (271 Reliquary bag), p. 287

Measurements: Bag is 31.5 cm x 26 cm (12.4” x 10.2”) Fringe is 16 cm (6.3”)

Gauge: 80 stitches and 70 rows = 10 cm (4”)

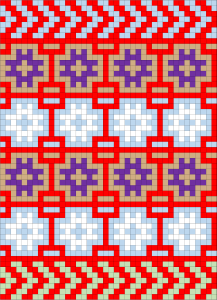

Colors: Violet, red, light green, white, beige, light blue

Sion relic-purse III (269 Reliquary bag), p. 286

Measurements: Bag is 23 cm x 19.5 cm (9.1” x 7.7”) Fringe is 16 cm (6.3”) Pattern repeat is 7.4 cm x 1.9 cm (2.9” x 0.75”)

Gauge: 50-60 stitches and 70 rows = 10 cm (4”)

Colors: Violet, red, light green, light blue, white, beige

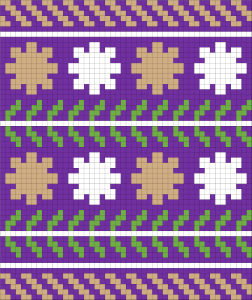

Sion relic-purse IV (272 Reliquary bag), p. 288

Measurements: Bag is 20.6 cm x 19 cm (8.1” x 7.5”) Fringe is 14 cm (5.5”) Pattern repeat is 3 cm x 1.7 cm (1.2” x 0.67”)

Gauge: 70 stitches and 70 rows = 10 cm (4”)

Colors: Violet, white, beige, light green

Sion relic-purse V (270 Fragment of a reliquary bag), p. 287

Measurements: Fragment is 20.5 cm x 21.8 cm (8.1” x 8.6”) Fringe is not present, because the lower half of the bag is missing. Pattern repeat is 6.5 cm x 2.3 cm (2.6” x 0.9”)

Gauge: 75 stitches and 90 rows = 10 cm (4”)

Colors: Red, light green, beige, white, violet, light blue

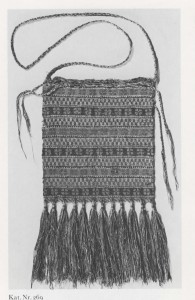

Chur purse (92 Reliquary bag), p. 91

Measurements: Bag is 34 cm x 24.5 cm (13.4” x 9.6”) Fringe is 13 cm (5.1”) Pattern repeat is 12 cm x 12-13 cm (4.7” x 5.1”)

Gauge: 90 stitches and 70 rows = 10 cm (4”)

Colors: Red, light blue, dark blue, white, beige, green

IV. Recreating a Sion-style purse

I chose Sion relic-purse III for my first attempt at recreating one of the Sion purses. To get the appropriate gauge (50-60 st to 10 cm/4”), I needed to use size 00000 (5/0) needles, which are 1 mm in diameter. For reference, the knitting website Ravelry has a database of over 400,000 patterns, with the largest percentage of patterns using size 6 needles. On size 6 needles, a knitter could reasonably expect to get 21-24 stitches to 10 centimeters. When using standard commercial yarn, even the smallest common gauge range, for size 000-1 needles, is approximately 33-40 stitches to 10 centimeters.

For the thread, I chose Halcyon Yarn’s 2/30 Gemstone Silk. The 2/30 designation indicates that it is 2-ply and the single plies equal 30 times the standard length of 560 yards, or 16,800 yards. The larger the second number is, the thinner the yarn is. This yarn was also spun in the same way as silk threads from the time period of the Sion purses, with a Z-spun single and the two threads plied together with an S-spin.

With metal knitting needles and silk thread, there is little resistance to keep the stitches on the needles. The needles I had on hand were 4” long, so I would recommend longer needles or a circular needle (though not period, it makes things a lot easier) to alleviate the slipping issues. There are also not point protectors in small enough sizes for 5/0 needles, so I cut pieces of a cork to use for that purpose.

About halfway through knitting the bag, I realized that working the ends of the yarn in as I knit the bag would save me a lot of weaving in work in the end. There are multiple ways of doing this, but my main technique was just carrying the ends along as if they were part of the colorwork, and twisting them behind the working yarn every three or so stitches. Some of the different ways to work the ends in can be found here.

To finish the bag, I wove in and trimmed all of the ends, and then blocked the bag. Blocking serves two purposes – to gently shape the knit object, and to even out stitches. To block the bag, I soaked it in water and then used metal rods woven through the stitches to shape it into an even rectangle, then let it air dry. The blocking made a big difference in the appearance of the purse. After it was blocked, I attached 12 tassels, then used fingerloop braiding to make a drawstring and a carrying loop. The only pictures I have found of this particular purse are in black and white, but a picture of the Chur purse shows that the tassels, drawstring, and loop were all made of multiple colors, so I concluded that they could be the same on this purse. It is unclear from the pictures what technique was used to make the strings, so I decided to use fingerloop braiding, since I already knew how to fingerloop braid. The drawstrings are “A Round Lace of 5 Loops” and the carrying loop is “A Broad Lace of 5 Loops,” both of which were found on medieval purses.

After completing the purse, I discovered that my purse measured considerably smaller than the original. Sion Purse III measured approximately 9.1″ x 7.7″ and my recreation measured 5.75″ x 5.25″. The vertical repeats were the same, the horizontal repeats were the same. I measured the gauge of my purse, and it had a gauge of 88 st and 92 rows = 4″. The extant piece had a gauge of 50-60 st and 70 rows = 4″. I realized that the gauge swatch I had knit was in one color. When knitting colorwork (two or more colors), the knitting will tend to have tighter gauge than when knitting with a single color. Lesson learned: Knit your gauge swatch in the same manner as you will knit your project. If it’s in the round, do it in the round (which I did). If it’s colorwork, do it in colorwork (which I did not). I could have knit this project with needles the next size up, if not larger. However, The Sion and Chur purses do vary in gauge, and one purse has gauge of 75 st and 90 rows = 4″ while another has gauge of 90 st and 70 rows = 4″. So while my gauge is not accurate for the specific purse I was recreating, it is historically accurate for other knit purses.

My next goal is handspinning silk to knit a purse of my own design. Silkworm cocoons have been used to make silk for thousands of years, and there are two basic varieties: wild and cultivated. Wild silkworms, since they feed on whatever leaves happen to be available, do not produce a uniform fiber. They are also usually harvested after the silkworm has emerged from its cocoon, so the cocoon can not be harvested as a single thread, but results in multiple pieces and makes it more difficult to process for spinning purposes. Cultivated silkworms may be referred to as Bombyx (their scientific name) or Mulberry (after their food source), and produce a much finer and smoother fiber. These silkworms have been bred in controlled environments for over 5,000 years. Since they only eat Mulberry leaves, there is much greater consistency across cocoons, and the silk is harvested before the silkworm emerges, so the cocoon can be processed in one unbroken strand. I was interested in what the difference really looked like when thread was spun and knit, so I tested it out. In the below picture, the reddish pink is a wild silk, and the white is a cultivated silk. The difference between the two types is readily apparent when presented side-by-side. To make the most reliable comparison, I spun and plied each silk within days of each other, trying for the thinnest spin I could manage without breaking, and knit them on the same size needles. The wild silk was more difficult to spin, and spun thicker despite my attempts to draft it to a smaller thread. It was dyed, which the cultivated was not, but it was commercially dyed, so the process shouldn’t have affected the fibers in an adverse manner.

In addition to the handspinning, I also decided to try my hand at natural dyeing. I have done a couple experiments with natural dyes, namely with black walnut hulls, alkanet root, and onion skins, using alum as a mordant. Mordants are used to help dyes adhere to the fiber, and alum was a commonly used mordant in the middle ages. All three of the dyestuffs I used were available and used during the middle ages. The alkanet root and black walnut hulls were purchased as powders, and I gathered the onion skins to create the dyebath myself. In the below images, the smaller skeins are commercially spun silk while the larger skeins are my handspun. From left to right, the colors were obtained with alkanet root, black walnut hulls, and onion skins. My next step with this project will be charting a design with a medieval aesthetic and knitting a purse with my own handspun and natural dyed silk.

The knit purses that were found in Sion and Chur, Switzerland and dated to the 14th Century were likely reliquary bags, used to hold important religious objects. They were made from silk, a prized material, and were found with other religious items in cathedrals. Because several paintings of the same period depict Madonna knitting, I believe that they are the work of a woman, who made them to show her devotion to the church. Because they have slightly different gauges, they were likely knit over many years, or with different sized needles. They are intricately designed, finely knit, and show a high level of skill. The knitter who created them likely also made other objects, since colorwork knitting and knitting on very small needles are skills that take considerable time and practice to get to a competent level.

VI. References

Barber, E.J.W. Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Benns, Elizabeth, and Gina Barrett. Tak v Bowes Departed: A 15th Century Braiding Manual Examined. Great Britain: Soper Lane, 2005.

Boehm, Barbara Drake. “Relics and Reliquaries in Medieval Christianity.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (originally published October 2001, last revised April 2011). 14 May 2017.

Crowfoot, Elisabeth, Frances Pritchard, and Kay Staniland. Textiles and Clothing, C.1150-c.1450. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell, 2006.

Gilbert, Rosalie. “Medieval Dyestuffs, Dyeing & Colour Names.” Rosalie’s Medieval Woman. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Apr. 2017.

Historic Enterprises. “Colors.” Historic Enterprises. Historic Enterprises, n.d. Web. 03 Apr. 2017.

Laning, Chris. “Medieval Masterpieces: The Purses of Sion.” Knitting Traditions Spring 2013: 74-76.

Lins, Joseph. “Sion.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 16 May 2017.

Logan, F. Donald. A History of the Church in the Middle Ages. London: Routledge, 2013. Web. 14 May 2017.

Ottaway, Patrick, and Nicola S.H. Rogers. Craft, industry and everyday life: finds from Medieval York. York: Council for British Archaeology, 2002.

Rutt, Richard. A History of Handknitting. Interweave, 1987.

Schmedding, Brigitta. Mittelalterliche Textilien in Kirchen Und Klöstern Der Schweiz: Katalog. Bern: Stämpfli, 1978.

Schulenburg, Jane Tibbetts. Holy Women and the Needle Arts: Piety, Devotion, and Stitching the Sacred, ca. 500- 1150. In Katherine Allen Smith and Scott Wells (Ed.), Negotiating Community and Difference in Medieval Europe: Gender, Power, Patronage, and the Authority of Religion in Latin Christendom (pp. 83-110), 2009.