Arts & Sciences Research Paper #11: Jewish Carolingian Fighters: The Jewish Fighting Freeholders of Carolingian Southern France

Our eleventh A&S Research Paper comes to us from Lord Gideon ha-Khazar, until very recently of the Barony of Dragonship Haven and now of the Barony of the Middle Marches, and who did most of this research while he was a citizen of our fair kingdom. He examines the history of a group of people many of us know very little about – European Jewish freeholders who fought in battles alongside their non-Jewish counterparts – and provides fascinating historical support for medieval Jewish fighting personae. (Prospective future contributors, please check out our original Call for Papers.)

Jewish Carolingian Fighters: The Jewish Fighting Freeholders of Carolingian Southern France

“Quapropter sumus dolore tacti, usque ad mortem anxiati, cum cognovissemus per teipsum, quod plebs Judaica … infra fines at territoria Christianorum allodia haereditatum in villis et suburbanis, quasi incolae Christianorum, possideant per quaedam regum Francorum praecepta.” (Migne vol. 129 p.857 and Jaffe 288)

“Therefore we are struck with sorrow, anxious to death, since we have learned through you that the Jews … possess allodial lands within Christendom in towns and outside them, like Christians, through certain grants of the kings of the Franks” (Chazan 188)

— Pope Stephen III to the Archbishop of Narbonne and “all magnates of Septimania and Hispania”, 768 CE

In 768 Pepin, Carolingian King of the Franks, recognized Jews’ rights to own land in what is now southern France. Since the lands were held in allod (owned outright instead of feudally) and in Frankish law all allodial landholders had to fight when called, Jewish fighters took part in Carolingian wars (including Charlemagne’s Roncesvalles campaign) and helped garrison lands taken from the Muslims.

Thus SCAdians have documented historical bases for having openly Jewish fighting freeholder personae from Carolingian (8th-9th century) southern France and its Spanish March. Furthermore, the region was on Radanite Jewish trade routes extending all the way to China and Narbonne was a center for scholarship, so one could historically justify having fighter-traveler or fighter-scholar personae from those periods as well.

Contents

A Series of Alliances

Allodial Landholding in Frankish/Carolingian Law

The Bigger Picture

The Quiet Fade to Silence

Continuing the Legacy

One Last Call to Battle

Persona Opportunities

Conclusion

Appendix: Pope Stephen’s Epistle

Bibliography

A Series of Alliances

After the fall of Rome some European Jews formed a series of “troops for tolerance” alliances, fighting for non-Jewish tribes or kings who were religiously tolerant.

The first troops-for-tolerance alliance was with the Arian Christian Goths of what are now Spain, Italy, and southern France. After Ostrogothic King Theodoric the Great’s 493 pronouncement that “We can not command religion, for no man can be compelled to believe anything against his conscience” (Graetz, 30), Jewish troops helped defend the city walls of Arles during Frankish King Clovis’ 507-8 siege and of Naples when it was attacked in 537 by Byzantine and Frankish forces. In his eyewitness account of the attack on Naples, the Byzantine historian Procopius wrote “But on the side of the circuit-wall that faces the sea, where the forces on guard were not barbarians, but Jews, the [attacking] soldiers were unable to either use the ladders or to scale the wall … [the Jews] kept fighting stubbornly, although they could see the city had already been captured, and held out beyond all expectation against the assaults of their opponents” (Procopius, Book V, paragraphs 100-101).

In 554 Ostrogoth Italy fell to the Byzantines and in 589 the Visigothic kings of Spain began passing increasingly harsh anti-Jewish decrees, but in Visigothic Septimania – the region around Narbonne in what is now southern France – the Jewish-Gothic alliance continued for over two centuries after King Theodoric’s pronouncement. In Septimania it was the fiercely independent Visigothic nobles who ruled, not the distant and often short-reigned kings over the mountains in Spain, and the local nobles found the Jews too useful to change the arrangement. Between the difficulty of enforcing royal decrees in Septimania and the royal dependence on Jewish troops’ helping defend the frontier (Graetz, 45) the Visigothic crown often explicitly exempted the Jews of Septimania from the harsh decrees they imposed on the Jews in Spain itself.

These decrees, such as King Egica’s 694 order that all Jewish children aged seven and older be taken from their parents and raised as Christians (Dubnov, vol. II, 526), led directly to the second troops-for-tolerance alliance: with the Muslims who in 711 CE invaded and quickly conquered Catholic Visigothic Iberia. Many of the invading troops were Jewish refugees from Spain serving under their general Kaulan al-Yehudi (Wolkoff, 25) and Muslim commanders often used them to garrison conquered cities, freeing up their own forces for more glorious field operations. The 17th-century Arab historian Al-Makkari specifically mentioned Cordoba, Toledo, and the citadel of Elvira as garrisoned by Jews, writing “Whenever the Moslems conquered a town, it was left in the custody of the Jews, with only a few Moslems, the rest of the army proceeding to new conquests; and where the Jews were deficient a proportionately greater body of Moslems was left in charge” (Al-Makkari, 280-282). This alliance helped create three centuries of mostly peaceful co-existence between Muslims and Jews, the Golden Age of Jewish culture in Spain (al-Andalus).

Carolingian Frankish King Pepin thus built on a long history when he allied with the Jews of southern France, and like the other alliances his was based on a need for more troops and loyal supporters. Although Pepin’s father Charles Martel had stopped the Muslim advance in 732, the Aquitaine and much of the southern coast were held by either Muslims or independent Christian rulers — some of whom like Maurontus, Duke of Provence, had allied with the Muslims against the Carolingians (Rogers, “Avignon, Siege Of”). In 759 Pepin managed to take the coastal city of Narbonne, but only after a seven-year siege. King Pepin sought to make better progress, and to do so he promised the Jews of Narbonne and the surrounding areas that he would reverse the old Merovingian Frankish dynasty’s anti-Jewish policies and grant Jews rights – including the right to own their own land — in return for Jewish support.

No text of the promise itself survives. We do not even know for certain the year it was made. Professor Arthur Zuckerman, in his book A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France, suggests that Muslim Narbonne had a Jewish garrison that surrendered the city to Pepin after seven years of siege in return for Pepin’s promise of Jewish rights. The timing is right, the suggestion is consistent with both Muslim and Gothic use of Jewish troops, and Zuckerman points out that French medieval histories such as the 13th-century Karoli Magni ad Carcassonam et Narbonnam explicitly say it was the Jews who handed Narbonne to Pepin.

What we do know for certain is that in 768 CE, one year after he conquered the Aquitaine using Narbonne as a base of operations, King Pepin kept his promise – and that Pope Stephen III immediately and unsuccessfully demanded that King Pepin break it. The Pope’s demand, which has survived, also said that the Jewish lands were allodial, a statement with significant legal implications.

Back to Top

Allodial landholding in Frankish/Carolingian law

Frankish law recognized three kinds of landholding. One was the benefice or fief, what we recognize as the standard feudal arrangement wherein the king owns all the land but “temporarily” gifts portions to vassals in return for services rendered. The second was tributary, in which the cultivator actually didn’t own the land he worked but paid rent to the one who did.

Allodial lands, in contrast, were independently owned – in its purest theoretical form without any obligations of taxation or service to higher authority whatsoever. Franks who had conquered what is now France and received allodial lands as a reward were free from taxes and all obligations except one: to personally bear arms and march against the enemy when summoned. “So stringent was the law of military service, that even the holders of ecclesiastical property were originally not exempt from it” (Jervis, 130). Non-Frankish inhabitants who held allodial lands (usually from Roman times) had the same arrangement, except that up to later Merovingian times they still had to pay the land tax (impot foncier).

Thus Carolingian allodial landholding implies military service, and indeed after the 768 decree we see Jewish fighters in Carolingian armies. In 778 the Count of Narbonne, whose troops included Jewish allodial freeholders, joined Charlemagne in his first attack on Spain – the campaign featured in the medieval epic The Song of Roland. Although the rearguard was defeated at Roncesvalles and as a result Charlemagne removed nine counts, the Jewish troops must have performed well because the Count of Narbonne kept his job and Charlemagne would use Narbonnaise levies again for his 802-803 campaign against Barcelona. Then in 805 Count Burrellus of Vich (aka Vic or Ausona, 20 miles north of Barcelona) helped lead the Carolingian attack on Tortosa using the Jewish freeholding troops he’d colonized and garrisoned Vich with eight years before. (Bachrach 1993, 15-18, and Bachrach 1977, 68-70).

In 1245 Rabbi Meir b. Simeon would remind the French king of this military service, writing “[Charlemagne] and his successors conquered many lands all with the help of the Israelites who were with them in fidelity with person and property so that they themselves entered into the thick of battle and sacrificed their lives to rescue kings and princes who were with them” (Zuckerman, 65-66).

Both Carolingian support for Jews and senior Church opposition continued after Pepin and Charlemagne, even as the Carolingian Empire began to break up. In 846 a Church council gave King Charles the Bald a series of proposed laws that would have taken Jewish children from their families to be raised by Christians, banned Jews from holding any governmental office or pleading their cases in Christian courts, and prevented Christians from dining with, working for, or buying from Jews. King Charles rejected all these proposals, declaring that Jews were to be treated as any other free person (Bachrach 1977, 106-111).

There were strong practical reasons for Charles’ decision. A general policy of tolerance had given the Empire the support of more groups than just the Jews: in 768, the year Pepin kept his promise, he also declared a Capitulary giving all denizens of newly conquered Aquitaine the right to live by their own laws (Zuckerman, 44). After that declaration, the Carolingians would keep their hold on the Aquitaine. And Charlemagne’s 778 Spanish campaign was sparked by the Muslim wali of Barcelona’s offer of submission while remaining Muslim in return for protection from the Muslim Umayyad emirate ruling most of Spain. So yes, Jews filled vital roles in the Empire from international trade to minting coins – but the freedom letting them do so came from a wider Carolingian approach to governance.

Back to Top

The Bigger Picture

Carolingian policy was not unique in this regard. Consistently, the medieval rulers who offered troops-for-tolerance deals to Jews offered improved opportunities to other religions or to lower classes as well. When Christian Spain and Portugal needed more troops for the Reconquista and offered increased social status to Jews who fought mounted and armored for the Crown, they also offered the status of “commoner-knight” to commoners who did the same (ha-Khazar, 7-8). In 1398 when Lithuania settled almost 400 Karaite Jewish families to reinforce its border with the Teutonic Order (Baron, 8-9), it also still kept full rights for its pagans despite having officially converted to Catholicism just twelve years before. The Dutch who supported Jewish privateers attacking Spain (Kritzler, 73-77) had also proclaimed freedom of religion as part of their nation’s founding document – the 1579 Union of Utrecht.

This does not mean that such rulers were willing to treat all other religions or the lower classes as full equals. Charlemagne had Jewish troops and allied with the Muslim Abbasid Caliphate against the Muslim Umayyads of Spain but still fought long, bloody wars against the pagan Saxons. The Iberian “commoner-knights” were given social and tax benefits but still remained commoners, below the noble knights in status. Jews and Christians in Golden Age al-Andalus reached prominent positions while keeping their own religion but were still subject to limitations as dhimmis – non-Muslims living under Muslim rule.

It does mean, however, that whether through simple human decency or calculated self-interest some medieval rulers – more than are commonly realized – offered opportunities beyond the medieval norm to religious minorities or to lower classes who could strengthen their realms in return. The Carolingians were such rulers, the Jews of Carolingian southern France were a minority willing to provide soldiers, and thus the Jewish-Carolingian troops-for-tolerance alliance was forged.

Back to Top

The Quiet Fade to Silence

As the Carolingian Empire aged and broke up, mention of military Jews in southern France simply stopped.

This is odd because no decree made allodial Jews stop serving or kept them from bearing arms. Furthermore, while Jewish allodial lands shrank as the post-Carolingian French monarchs expanded their reach and took more and more lands for themselves or for the Church, and while the Carolingians lost Vich during the Catalan revolt of 826-828 (Lewis, 46, 93), many Jewish allods remained. In 1173 – four centuries after Pepin’s decree – the traveler Benjamin of Tudela recorded that the Narbonne Jewish community’s head “possesses hereditaments and lands given him by the ruler of the city, of which no man can forcibly dispossess him” (Tudela, 2). A viscountal decree confirms this still existed in 1217 (Zuckerman, 170). Religious tolerance by medieval standards had also continued: when the Bishop of Toulouse asked in 1207 why Cathars and other non-Catholic sects were not expelled from the region, Sir Pons Adhemar of Roudeille replied “We cannot: we were brought up with them, there are many of our relatives amongst them, and we can see that their way of life is a virtuous one” (Puylaurens, 25).

The most likely explanation can be found in changes in Carolingian law. Throughout the Carolingian period numerous laws gave allodial landholders increasing ways to exempt themselves from the “personal military service” requirement – a modern equivalent would be the way many Vietnam-era American college students from well-connected families legally avoided being sent overseas to a combat zone. By the time of Charles the Bald, freeholders could only be mustered in case of foreign invasion (Jervis, 130).

This mattered to Jews because when the Empire ended the social environment also changed. Allodial Jewish lands belonged to neither king nor Church, and not coincidentally the message began being spread how Jews were an “other” and thus a legitimate target. The 11th-century epic poem The Song of Roland, for example, re-painted Charlemagne as an avenger of Muslim atrocities (even though the actual ambushers at Roncesvalles were Christian Basques, not Muslims) who forcibly mass-converted Jews in stanza 266 (something Charlemagne never did) – actions all lauded by the poem’s author.

In such an environment, taking the field meant having your back to armed people who saw you as the enemy – indeed, Crusaders often killed European Jews before going on to kill Middle Eastern Muslims. Given a choice between “serve and probably be fragged” or “take the exemption” one can understand very quietly choosing the latter.

Back to Top

Continuing the Legacy

The fighting freeholders’ descendants may have carried on their ancestors’ legacy in a small but fascinating way.

Tosafot (aka Tosafos) were legal rulings and commentaries on the Talmud dating from 12th– and early 13th-century France. In discussing roughhouse games during celebrations, Tosafot Sukkah 45a says “From here we can learn that when the young people ride on horses to greet the groom and bride and joust [for sport] and sometimes tear each others’ clothing or damage the horse, there is no requirement to reimburse because this is the commonly accepted way to celebrate at a wedding.” (Flug, 2)

This does not mean French Jews commonly celebrated with fully armored full-contact jousting – that certainly would have been noticed and mentioned elsewhere. Another “mental picture” is therefore in order.

Let’s see … medieval-type fighting for fun? Check. Weapons solid enough to cause occasional damage but not (usually) serious injuries? Check. Skill required? Check – just ask any SCAdian equestrian if she would lend her horse to a totally unskilled partier.

Medieval Jewish SCAdians, anyone?

Back to Top

One Last Call to Battle

After the Carolingian Empire fell, southern France escaped for a while the horrors of religious-based war. During the First and Second Crusades there were massacres in Jewish communities throughout the Holy Roman Empire and Northern France but not in southern France. How much that was due to protection by the still-pro-Jewish southern counts and whether there was any quiet deterrence by the freeholders’ descendants’ ability to defend themselves are intriguing questions worthy of further research.

However, four centuries after the Jewish freeholding fighters faded from the battlefield record, the Albigensian Crusade hit southern France. In 1210 the Bishop of Toulouse formed a Grand White Brotherhood to raid the homes of the city’s Jews and Cathars. William of Puylaurens, who served in the Bishop’s entourage, recorded in his Chronicle that the surrounding areas then raised a force (called the Black Brotherhood) to fight the White Brotherhood, “with standards raised and the use of armoured horses” (Puylaurens, pp. 35-37).

Puylaurens does not indicate either the presence or absence of Jews in the Black Brotherhood, though he does say that Jews fortified and defended their homes against the White Brotherhood’s attacks. Still, one can reasonably argue that when other southern landholders armored up to protect their neighbors’ homes, at least some descendants of the Carolingian freeholding fighters may have traded their sport swords for real ones and ridden out with them.

Back to Top

Persona Opportunities

As can be seen from the above, Jewish freeholding fighter personae are solidly historically supportable during Carolingian times and plausible through the early 1200s. During these periods, one can also historically justify personae who are not just fighters but world travelers and/or scholars as well.

The Fighter-Traveler Persona: Some SCAdians want personae who visited many far-flung countries. Fortunately, Carolingian France was on the trade routes of the Radanites, Jewish merchants whose routes extended west to Morocco and east to India and China. Obaidallah ibn Khordadhbeh, whose 817 CE Book of Ways and Kingdoms detailed these routes, wrote “These merchants speak Arabic, Persian, Roman [i.e. Greek and Latin], the Frank, Spanish, and Slav languages … On their return from China … [some] go to the palace of the King of the Franks to place their goods” (Adler, 2-3). Such merchants had an obvious use for fighters.

The Fighter-Scholar Persona: Charlemagne encouraged learning in his Empire, founding schools and ordering that his children be educated even though he himself never learned to write. Narbonne benefitted from this effort – Ibn Daud’s 1161 Book of Tradition recorded that at Charlemagne’s request Caliph Harun al-Rashid had sent a noted Babylonian scholar to Narbonne, and by the 12th century Narbonne had become a major center of Jewish scholarship and science. Thus a fighter-scholar persona – following both the Jewish tradition of learning and Charlemagne’s own lead – would have been eminently plausible.

Back to Top

Conclusion

Throughout the Middle Ages a series of rulers offered Jews rights and received Jewish support in return – sometimes including military support. In 768 CE King Pepin became one of these, granting the Jews of what is now southern France the right to own land allodially – i.e. as freeholds – in return for their being required to provide personal armed service when called. These freeholders served in Carolingian armies, joining Charlemagne in his Spanish campaigns and helping to garrison cities against the Muslims.

Under the Carolingians trade and learning grew, giving SCAdians historical support for Jewish fighter personae who are not merely fighters but travelers or scholars as well.

As the Carolingian Empire aged and fell, records of Jewish allodial fighters simply stop – yet most Jewish freeholding continued and the fighters were not disarmed. I am still searching for proof, but given the spread at the time of popular stories painting Jews as targets I think that the freeholders just quietly took advantage of the draft exemptions and joined many of their fellow landholders in retiring from the battlefield.

By then they had made a lasting difference. Almost 80 years after Narbonne helped Pepin win the Aquitaine, a Carolingian king kept faith with his predecessors’ troops and quashed the Church’s attempt to take Jewish children from their parents. Over two centuries after Pepin, First and Second Crusaders would massacre Jewish communities in northern France and Germany — but not in southern France where the allods still existed. And four centuries after Pepin, Jews could still sport-fight for fun where their ancestors had had to fight for real.

The Jewish-Carolingian troops-for-tolerance alliance had worked.

Back to Top

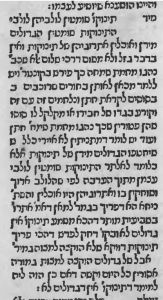

Appendix: The full text of Pope Stephen III’s Epistle on the Allodial Jews of Narbonne, 768 CE

Original Latin text from Jacques Paul Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus. Series Latina. Volume CXXIX, col. 857. For the English I used Chazan’s translation (Chazan, 188) for all sections he translated, Zuckerman’s translation (Zuckerman, 72) for the greeting, then translated the remaining sections myself.

| Original Latin | English Translation | Translator |

| AD ARIBERTUM NARBONNENSEM ARCHIEPISCOPUM. Queritur factam esse Judaeis potestatem allodia possidendi. |

TO ARIBERT, ARCHBISHOP OF NARBONNE Protesting the Jews’ acquiring the power to hold allodial lands |

Author |

| STEPHANUS papo ARIBERTO archiepiscopo Narbonae, et omnibus potentatibus Septimae et Hispaniae salutem. | Pope Stephen To Aribert Archbishop of Narbonne, and to all magnates of Septimania and Hispania. | Zuckerman |

| Convenit nobis, qui clavem coelestis horrei vicibus apostolicis suscepimus, etiam omni pestilentiae gregis divini fidei medicinam porrigere: quod si non possumus modios tritici, at saltem cestarium [sextarium] valeamus impendere. | It comes to us, we who have undertaken our turn with the apostolic key to the heavenly storehouse, also to extend the medicine to all plagues of the divine flock of the faith: because if we are unable [to extend] pecks of wheat, at least we may be strong enough to extend at least a pint. | Author |

| Quapropter sumus dolore tacti, usque ad mortem anxiati, cum cognovissemus per teipsum, quod plebs Judaica Deo semper rebellis, et nostris derogans caeremoniis infra fines at territoria Christianorum allodia haereditatum in villis et suburbanis, quasi incolae Christianorum, possideant per quaedam regum Francorum praecepta: | Therefore we are struck with sorrow, anxious to death, since we have learned through you that the Jews – ever rebellious to God and disparaging of our practices – possess allodial lands within Christendom in towns and outside them, like Christians, through certain grants of the kings of the Franks: | Chazan |

| quia ipsi inimici Domini quae … sunt, ei periculose mercati sunt: | Because the enemies of the Lord themselves which… they are, they have dangerously traded: | Author |

| Et quod vineas et agros illorum Christiani homines excolant: et infra civitates et extra, masculi et feminae Christianorum cum eisdem praevaricatoribus habitantes, diu noctuque verbis blasphemiae maculantur, et cuncta obsequia quae dici aut excogitari possunt, miseri miseraeve praenotatis canibus indesinenter exhibeant: praesertim cum huiusmodi patribus Hebraeorum promissa ab electo iurislatore illorum Mose, et successore eius Iosue, his conclusa et terminata finibus, ab ipso Domino iurata et tradita istis incredulis, et patribus eorum sceleratis, pro ultione crucifixi Salvatoris merito sint ablata. Et revera praeceptor Ecclesiae gregibus orthodoxis significat inquiens: Quae societas luci et tenebris? quae conventio Christi ad Belial? aut quis consensus templo Dei cum idolis? (II Cor. VI.) Et summi consiliarius verbi admonet, dicens: Si quis dixerit ei Ave (II Ioan. XI), etc. | and that these miserable men and women must exhibit continually to the aforesaid dogs every allegiance which can be formulated and devised: particularly since promises concluded and defined for the Jews’ ancestors by their chosen leader Moses and his successor Joshua and sworn to and transmitted by God Himself to these unbelievers and their wicked ancestors should properly be negated in punishment for the crucifixion of the Savior. Indeed the teacher indicates to the flocks of the orthodox Church, saying: “Can light consort with darkness? Can Christ agree with Belial, or a believer join hands with an unbeliever? Can there be a compact between the temple of God and the idols of the heathen?” (II Cor. 6:4-16) and the counselor of the sublime word admonishes, saying: “Anyone who gives him a greeting is an accomplice in his wicked deeds.” (II John 11), etc. | Chazan |

| Desunt caetera. | The others are failing/abandoned. | Author |

Back to Top

Bibliography

Primary Sources (including collections of primary source documents)

Adler, Elkan Nathan (ed.). Jewish Travelers in the Middle Ages: 19 Firsthand Accounts. New York: Dover Publications, 1987. Originally published in 1930. Print.

Al-Makkari, Ahmed ibn Mohammed. The History of Mohammedan Dynasties in Spain. 1629; translated from originals in the British Library by Pascual de Gayangos, (W.H. Allen and Co., London, 1840). Print.

ibn Daud, Abraham. Sefer ha-Quabbalah – The Book of Tradition. 1161. Gerson D. Cohen (trans.), The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1967. Print.

Jaffe, Philippus (ed). Regesta pontificum romanorum ab condita ecclesia ad annum post Christum natum MCXCVIII. Vol 1. Catholic Church. Print and online.

Marcus, Jacob Rader. The Jew in the Medieval World – A Source Book: 315-1791, Revised Edition. New York: Hebrew Union College Press, 1990. Print.

Migne, Jacques-Paul. Patrologia Latina. Paris: Imprimerie Catholique, 1841-1855. Print and online.

Procopius of Caesaria. History of the Wars, 550 CE. H.B. Dewing trans., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914. Print and online.

Puylaurens, William. The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: The Albigensian Crusade and its Aftermath. 1275. W.A. and M.D. Sibly (Trans), The Boydell Press, Woodbridge (in Suffolk, UK), 2003. Print.

Tudela, Benjamin of. The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela. 1175 CE. Marcus Nathan Adler trans. New York: Philipp Feldheim, 1907. Print and online.

Secondary Sources

Bachrach, Bernard S. “On the Role of the Jews in the Establishment of the Spanish March (768-814)”. Essay XV in Armies and Politics in the Early Medieval West. Surrey: Ashgate Variorum, 1993. Print and Online.

Bachrach, Bernard S. Early Medieval Jewish Policy in Western Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977. Print.

Baron, Salo Wittmayer. A Social and Religious History of the Jews, Second Edition, Vol. XVI. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983. Print.

Chazan, Robert. Jewish Social Studies, vol. 37, no. 2. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975. Print and online.

Dubnov, Simon. History of the Jews from the Roman Empire to the Early Medieval Period. 4th Definitive Revised edition: Moshe Spigel (trans.), New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1968. Print.

Flug, Joshua. “Practical Jokes and Their Consequences”, Shabbat Table Discussions, Issue #20. New York: Yeshiva University, 2013. Print and Online.

Graetz, Heinrich. History of the Jews, Volume III. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1891. Print.

ha-Khazar, Gideon. “Jewish Near-Knights, or Why Were These Knights Different From All Other Knights?”, Tournaments Illuminated #196. Milpitas: The Society for Creative Anachronism, 2015. Print.

Jervis, William Henry. A History of France to 1852. London: John Murray, 1884. Print and online.

Kritzler, Edward. Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean. New York: Anchor Books, 2008. Print.

Lewis, Archibald. The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society 718-1050. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1965. Print and online.

Rogers, Clifford J. (editor). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. Print and online.

Wolkoff, Lew. The Compleat Anachronist #110: An SCA Guide to Jewish Persona. Milpitas: The Society for Creative Anachronism, 2001. Print.

Zuckerman, Arthur. A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France, 768-900. New York: Columbia University Press, 1972. Print.

Back to Top