A&S Research Paper #32: The Historical Ninja: Casting Light on the Shadows

Our 32nd research paper comes to us from Vindiorix Ordovix from the Shire of Mountain Freehold, written in honor of our current Majesty, Ryouko’jin Of-The Iron-Skies, and his Japanese Samurai persona. However, this paper is not about the Samurai military caste, but rather their “cultural opposites,” the Ninja. Dramatically featured in books, movies, and games, the historical Ninja is quite different than its counterpart found in modern popular culture.

The Historical Ninja: Casting Light on the Shadows

Vindiorix Ordovix (MKA Justin Davis)

To the modern person the word ninja conjures images of masked martial artists using supernatural powers to assassinate their targets. The ninja of modern fiction turns invisible, scales walls with incredible speed, and uses magic to accomplish their evil missions. The truth is far less fanciful, of course. In reality the ninja were members of certain Japanese clans who specialized in espionage, scouting, assassination and covert raiding. These clans were available for hire and came to prominence in fourteenth century CE feudal Japan.

The term ninja roughly translates to “stealer-in,” denoting someone skilled in stealth and concealment (Masaaki, 1988, pp. 1-2). Another proper term is shinobi, the difference being pronunciation. Much of the Japanese language is written using Chinese characters called kanji. When the characters are pronounced as the Chinese do it is ninja. When they are pronounced as the Japanese do, it is shinobi (Turnbull, 1992, pp. 10-11). Ninja are also referred to in a variety of period manuscripts by the types of actions they performed, such as kancho (spies), teisatsu (scouts), and the rather descriptive kagimono-hiki (sniffing and listening) (Turnbull, 1992, p. 11). Another nickname for them was kage (shadow) (Masaaki, 1988, p. 1). For the sake of this short paper the term ninja will be used throughout. The art the ninja practiced is called ninjutsu.

Origins

The original ninja of Japan in the 700s CE did not use the term. It was not until much later, around the 1400s CE, that the term was developed.

The people who were later referred to as ninja did not originally use that label for themselves. They considered themselves to be merely practitioners of political, religious, and military strategies that were cultural opposites of the conventional outlooks of the times. Ninjutsu developed as a highly illegal counterculture to the ruling samurai elite, and for this reason alone, the origins of the art were shrouded by centuries of mystery, concealment, and deliberate confusion of history (Masaaki, 1981, p. 7).

The ninja specialized in specific military functions requiring stealth and guile. To maintain a tactical advantage, to protect their identities, to keep their clans safe, and to foster an aura of the supernatural, the ninja purposefully remained mysterious.

The origin of the ninja is found in China, with the powerful Tang Dynasty in the early seventh century CE. Japanese leaders, artists, and monks visited China to learn from this dynasty, including its knowledge of warfare (Man, 2013, p. 7). Certain political dissidents fled their native China in the 700s CE and found sanctuary in Japan. They brought with them foreign knowledge including military strategies soon adopted by the Japanese (Masaaki, 1981, p. 8). The Chinese general Sun Tzu’s famous The Art of War is one such example of military knowledge introduced to Japan in this manner (Turnbull, 1992, pp. 12-13). Its chapter on spies served as inspiration for the later ninjutsu in Japan. A review of that chapter shows that the historical ninja took on a much wider variety of roles than their image in popular culture. Included below are descriptions of five different types of agents, listed here by their Japanese name (Sun Tzu, 2012, pp. 43-44):

- Inkan (local spies or native agents): local inhabitants who can provide information through personal knowledge

- Naikan (inward spies or inside agents): officials working within the enemy’s organization who can be paid for information

- Yukan (converted spies or double agents): spies turned against their employer

- Shikan (doomed spies or agents of death): expendable people fed false information and set loose to be captured and interrogated by the enemy

- Shokan (surviving spies or living agents): classic spies sent in to gather information on the enemy

Armed with such military strategies that were not familiar to Japanese culture the ninja were able to carve out a niche, providing various services unavailable elsewhere.

Belief System

Given the nature of their profession, it is easy to assume the ninja lacked honor or compassion. They spied, conducted sabotage, and assassinated people. Still, reconnaissance, espionage, and night attacks were (and remain) a necessary part of warfare. Ninja for hire provided Japanese feudal lords a way to accomplish these tasks without having to use their own people and risking dishonor.

Perhaps because ninja performed actions considered dishonorable by wider Japanese society ninjutsu included spiritual refinement as one of the skills to train. Someone who committed violence for a living and lived outside accepted societal standards needed a moral handrail to keep themselves centered. This short poem from the 1676 ninja manual the Bansenshukai provides an example of the moral lessons taught to ninja. “If a shinobi steals for his own interest, which is against common morals, how can the gods or Buddha protect him?” (Cummins & Minami, 2013, p. 33).

Ninja filled a niche within Japanese society, but true to wider Japanese culture maintained their sense of honor and justice. Killing an enemy was acceptable, but murder was not. Using your skills to benefit your clan and country was appropriate but using them for selfish reasons was met with severe penalties. Like any profession that walks close to death, the ninja balanced their deadly lifestyle with a spiritual and ethical code.

Structure and Training

There was a rigid structure within ninja clans, designed to maintain the secrecy needed for an organization conducting espionage. At the top was the jonin (high man) who ran the organization and decided what contracts the organization would accept. Below the jonin were chunin (middle man) who served as an intermediary between the jonin and those ninja who executed the missions. Chunin assigned individuals to contracts. The lowest level was the genin (low man). The genin were akin to the shokan as described by Sun Tzu, they were the trained field agents who conducted the organization’s clandestine operations (Hayes, 2001, pp. 24-25). Given the nature of their profession, secrecy was paramount. This cellular structure insulated the leadership from discovery. Chunin might never know they took orders from the same jonin. A genin certainly did not know the identity of a jonin and so could not betray their masters if captured.

The genin are what we think of when we imagine a ninja. They were the ones who spied, scouted, conducted ambushes or raids, and sometimes assassinated targets. A 1656 Japanese military manual lists the following requirements for those selected to be genin (Cummins, 2012, p. 16):

- Those who look stupid but are resourceful and talented in speech or are witty.

- Those who are capable and act quickly and who are stout [and can endure]. Also those who do not succumb to illness.

- Those who are brave and open-minded and those who know much about certain districts and people all over the country, with the addition of being eloquent.

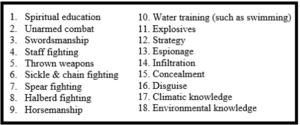

Those selected as field agents trained in the eighteen skills listed in the box to the right (Masaaki, 2004, p. 22). These skills provided the ninja a wide range of abilities ranging from spying or scouting to assassination and battlefield combat.

Those selected as field agents trained in the eighteen skills listed in the box to the right (Masaaki, 2004, p. 22). These skills provided the ninja a wide range of abilities ranging from spying or scouting to assassination and battlefield combat.

Translations of existing historical ninjutsu manuals provide specific examples of the types of techniques and tools ninja commonly used. The 1676 manual Bansenshukai includes instruction on lockpicking, maintaining a “correct mind” (remaining honorable, benevolent, and loyal), commanding, disguises, and infiltration (Cummins & Minami, 2013, pp. vii-viii). The same manual also has notes on a wide variety of tools, such as a section on ladders. Regardless of the topic, this and other such extant manuscripts are written for the initiated, not for the layperson. Given the secrecy of their art, and the advantages afforded them by secret techniques, it was important the casual reader be unable to learn a skill simply by reading a scroll. Take this explanation of a certain ladder for example: “The cloud ladder: This is not a ladder in its own right. For a place you cannot reach with a tied ladder or a flying ladder, secure a flying ladder onto a tied ladder as in the drawing and use it to climb. This is called the cloud ladder. There are further things to be orally transmitted here” (Cummins & Minami, 2013, p. 319).

The comment “further details are to be translated orally” is found throughout authentic ninjutsu books and scrolls. The knowledge was written down to catalogue and reference it, but it was assumed the reader understood the portions left out, similar to how someone might keep shorthand notes in a personal cookbook, for example. These trade secrets gave the ninja a tactical advantage.

Clothing

The image of a ninja clad in black, with a hood and mask, and with a sword strapped to their back is so iconic that it bears discussion. This is a modern interpretation and is not how the ninja routinely dressed when conducting their missions.

Ninja dressed for the mission at hand. If their mission included direct combat they wore mail armor, either overtly or hidden under clothing (Masaaki, 2004, p.93). If their mission required stealth, such as when scouting in the wilderness or at night, they wore dark and dull colors (Masaaki, 2004, p. 90). If conducting espionage, the ninja might dress in disguise. The Shoninki lists seven disguises one should use, including such things as traveling monks, merchants, and street performers (Cummins & Minami, 2011, pp. 53-54). The Shoninki also provides instruction on how to further disguise oneself by wearing a jacket or cape to change one’s shape, and by using various pigments to change one’s facial appearance (Cummins & Minami, 2011, p. 76). It is possible a ninja might wear black clothing, perhaps with a hood and mask if operating at night, but this is not well documented.

Conclusion

The historical ninja were not the superhuman invisible warriors of modern myth. They did not turn invisible and run up walls using magic. They were also not soulless, bloodthirsty killers. Instead, they were a necessary part of Japanese culture, especially during the warring period in the fourteenth century CE. They excelled at clandestine operations and maintained a strict secrecy. They purposefully obfuscated their structure, identities, and abilities for their own protection and to cultivate a mysterious and supernatural reputation.

References

Cummins, A. (2012). In Search of the Ninja. Glouchester, GB: The History Press.

Cummins, A. & Minami, Y. (2011). True Path of the Ninja. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Publishing.

Cummins, A. & Minami, Y. (2013). The Book of the Ninja. New York, NY: Osprey Publishing.

Hayes, S. (2001). The Ninja and Their Secret Fighting Art. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Publishing.

Man, J. (2013). Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Masaaki, H. (1981). Ninjutsu: History and Tradition. Burbank, CA: Unique Publications.

Masaaki, H. (1988). The Grandmaster’s Book of Ninja Training. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books.

Masaaki, H. (2004). The Way of the Ninja. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Turnbull, S. (1992). Ninja: The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult. New York, NY: Sterling Press.

Tzu, S. The Art of War. (2012). New York, NY: Barnes & Noble.