Arts & Sciences Research Paper #29: Hippocras, or a Discussion on the Origins and uses of Spiced Wine. A Medicinal, a Tonic, and an Epicurean Delight.

Our 29th A&S Research Paper comes to us from THL John Kelton of Greyhorn. John is a journeyman with the EK Brewers Guild and the guildmaster of the Honourable Company of Fermenters of The Barony of Concordia of the Snows. In this paper he takes us through the long history of Hippocras, a simple drink of spiced, sweetened wine. Two redacted recepies for the drink are included at the end of his paper for those who are interested in trying to make some themselves.

If you are interested in submitting a research article to the EK Gazette please see our most recent Call for Papers for more information.

Hippocras, or a Discussion on the Origins and uses of Spiced Wine. A Medicinal, a Tonic, and an Epicurean Delight.

THL John Kelton of Greyhorn

Contents

- Manicum Hippocraticum

- The Biblical Era

- The Greek and Roman Era

- The Talmudic Era

- The Medieval Era

- Sugar and Spice

- The Banquet and Voideé: The evolution from medicine to luxury

- Appendix: Two Early English Recipes

- References

Hippocras (ipocras, ipocrist, ypocras, and multiple spelling variations) is a simple drink of spiced, sweetened wine. It is the ancestor of what we refer to as mulled wine, which includes Gløgg, Bishop, Glühwein and Sangria. There is period documentation and extensive archeological evidence of spiced wines across multiple regions and cultures as far back as 7000 BC in Jiahu, China. Hippocras may have originated as a medicinal, as a digestive, or as an elegant beverage. Considering the evidence, I think it most likely to have had a complex origin which encompassed all of these (Day, Hoolihan). The field is so broad that we will limit our discussion to those civilizations most likely (but not exclusively) to have influenced European food and medicine.

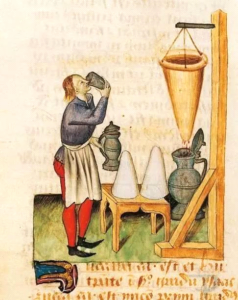

Before we continue, some background on the etymology of Hippocras. In Latin it is Vinum Hippocraticum – wine of Hippocrates. Although spiced wines were widely known in classical Greece, Hippocrates did not invent hippocras. The name actually refers to the filter used to remove the spices from the wine. The filter was a conical bag used by apothecaries known as a manicum hippocraticum, sleeve of Hippocrates, thus the eponymous name. Hippocrates of Kos (460-370 BCE) believing in the importance of pure water for his patients is said to have invented this device as a water filter (Baker, Day). Manuscript illustrations indicate that it could be used as a single filter or in a series of stacked filters.

Manicum Hippocraticum

The earliest biomolecular and archaeological evidence for grape wine in Europe, was found on pottery jars decorated with grape clusters excavated from a ca. 6,000–5,800 BCE mound in Gadachrili Gora, Georgia in the South Caucasus. Residue of resinated wine has also been found in potsherds dated to ca. 5400-5000 BCE excavated from a Neolithic village in Iran’s northern Zagros Mountains (McGovern 2017).

The Sumerians (c. 4500 – c. 1900 BCE) are the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now southern Iraq). From recovered cuneiform tablets, they are known to have used wine and beer mixed with various botanicals, minerals and animal parts as a disinfectant and medication (Nikolva pg 15).

East of Sumer lays Egypt and the Grave of Scorpion I c. 3150 BCE. When his tomb was excavated, archeologists found 700 imported jars containing a yellow residue. Analysis indicated the jars contained resinated herbed grape wine. The herbs included mint, coriander, and sage along with grapes and figs. Wine was not produced in Egypt during this time period but rather imported from the Jordan valley. Interestingly the figs were suspended on a string. Suspending an additive in wine is a technique mentioned by Arnald de Villanova some 4400 years later (McGovern – Arch, de Villanova pg 25). Considering the quantity, it is likely this was considered a prestige beverage and not simply medicine.

Egyptian physicians of the Middle Kingdom period ca 1550 BCE compiled the Ebers papyrus. The Ebers is likely to have been copied from earlier texts (and oral tradition). It contains one of the world’s oldest medical treatises including some 700 prescriptions (Britannica, von Klein). These often include herbs, fruits and vegetables such as lotus, coriander, watermelon, figs, onions, tree resins, myrrh, bryony, wormwood and even animal parts which are steeped or infused into a wine, beer, vinegar, milk, oil, water, or honey based, strained and then administered. The treatments could then be ingested, applied topically or used as an enema

The Biblical Era

One of, if not the earliest reference to spiced wine in the context of a luxury or aphrodisiac is in the biblical text Shir Hashirim; Song of Songs, c. 950 BCE – 5th cent BCE. Traditionally attributed to King Solomon c~950 BCE, modern scholarship dates it ca. ~ 5th BCE] (Britannica). Verse 8:2 “I would give you to drink some spiced wine, of the juice of my pomegranate.” In this instance the spiced wine appears to be proffered purely for enjoyment. The word interpreted as spiced, רֶֽקַח, is derived from a translation of perfumer, or spice mixture and the Hebrew word for wine, יַיִן (yayin) only applies to grape wine (Klein Dictionary). Unfortunately the text does not mention which spices were used or if the wine was sweetened.

During the Indian Vedic period, 2500 BCE-200 BCE, wine was worshipped as the liquid God Soma. The Hindus were among the first to record the use of wine as an anesthetic. The Hindu also state that wine taken indiscriminately causes disease.

Alexander the Great invaded India in 326-7 BCE and returned to Greece with Indian medical knowledge. Sharing medical knowledge was not one way. The Greek medical system enriched with local elements encountered a positive response and was incorporated into Indian practice. It is feasible that the Indians influenced Greek medicine which in turn had a profound influence on medical practice throughout the Western world (Sandler pg 25).

The Greek and Roman Era

Hippocrates of Kos

Hippocrates of Kos (460-370 BCE) was one of the leading physicians of ancient Greece whose theories and philosophy influenced medical practice for centuries. He is regarded as the father of modern medicine for discounting the role of the gods in favor of natural causes. Hippocrates made extensive use of wine as a health food, as a wound dressing and as medication. He advised cleaning wounds with wine and dressing them in clean wine soaked linen. In his text On Regimen, he commented on the specific types and amounts of wine suitable for different conditions. His treatments included wine containing various additives such as opoponax a type of gum resin, bryonia, carrot, grapes, myrrh, and honey (Regimen).

Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24–79), in The Natural History, also discusses spiced wines as medicinals, libations, offerings and for enjoyment (Pliny, Bostock). He comments that wine alone is efficacious as a remedy for disease but can be pernicious as a luxury if we are not on guard against excess. He refers to various wines used to promote both conception and abortion, induce sleep, as a laxative, and with the addition of rue as a cure for snake bites (Book XIV, Chaps 3, 7, 10, 22). Pliny discusses a wine known as Siraeum or Hepsema which is a boiled down must meant to be added to honey, while another is a sweet wine with honey and salt. (Book XIV, Ch 11). In Book XIV, chapter 15 Pliny comments on myrrh scented wine as the most esteemed among the ancient Romans and discusses adding honey and an array of botanicals including wormwood, pepper, and hyssop to wine which he refers to as peppered wine or confection wine (Chap 1,2 6). In these writings we see a crossover for herbed wine used for both enjoyment and as medicine.

Conditum or konditon (Greek κόνδιτον) was a spiced wine in ancient Roman and Byzantine cuisine. The Latin name roughly translates as “spiced” (Latdict). Recipes for conditum viatorium (traveler’s spiced wine) and conditum paradoxum (surprise spiced wine) are found in Apicus’ De re coquinaria (c. 1st cent AD). In fact Apicus begins with a recipe for conditum since it was commonly served at the start of a meal, in contrast with medieval hippocras served at the end. The recipe for conditum paradoxum includes wine, honey, pepper, mastic, laurel, saffron, date seeds and dates soaked in wine which is then clarified with charcoal (Apicus, pg45). Additional recipes include wine sweetened with honey and flavored with rose petals, violet petals, or citrus leaves.

Galen of Pergamon

Galen of Pergamon, (129AD – 216AD) was personal physician to the roman emperor Marcus Aurelius and is considered one of the greatest if not the greatest physicians of ancient Rome (Singer). His medical treatises and philosophy were the standard of practice and dogma well in to the late medieval and early renaissance period (Wasson). In de sanitae tuenda Galen recommends wool dipped in wine to cleanse wounds and as an anesthetic. In his world, poisonings and bites from venomous beasts were fairly common. This naturally led to the pursuit of a treatment that was capable of protecting a person against any kind of toxin. This so-called universal antidote was the theriac. For example, one formula consisted of viper’s flesh, opium, honey, wine, cinnamon, and more than 70 additional ingredients. It could be taken orally or applied topically (Karaberopoulos).

Much of Galen’s work was rooted in the ideas of his predecessor Hippocrates of Cos (460-375 BCE). This included the humoral theory where good health relies on a balance of the four humors, phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile. The key to this pseudo-medical system was balance. According to this theory, every individual has a unique humoral composition. If their body fell out of equilibrium, illnesses occur. Further, every food and beverage also had its own humoral affiliation. Foods could be hot, cold, dry or moist, with each characteristic influencing the body. This could be modified slightly based on its preparation. In practice doctors would prescribe specific foods to adjust their patient’s humoral balance. For example, if someone displayed too much heat, i.e. a fever, they might receive a bloodletting to reduce the amount of hot blood, and be instructed to eat cold foods, like salad or vegetables. If a person experienced indigestion from eating too much, they could take a hot and dry prescription, like pepper and wine.

Each humor has its own qualities which were associated with the four basic personality temperaments. Phlegm, cold and wet is associated with indolent, relaxed, peaceful individuals. Blood, hot and moist is sanguinary and associated with joyful, extroverted, active people. Yellow bile, hot and dry with passionate and courageous, while black bile, cold and dry with indolent, introverted (Food, Roos). Humors and thus health and personality were in turn affected by food and drink, which also had inherent humors. Wines could be considered hot and dry, although sweeter wine was moister. Galen felt that wine could improve melancholy and aggravate the passionate. However the very warmth of certain types of wine could aggravate some medical conditions. Further the beneficial vs. harmful effect of wine could vary according to the age and temperament of the individual. Children should not have wine whereas it was recommended for the elderly. Galen advised against wine for those with a hot nature since it produces heat and dryness, for them he recommended water. Women who had a cold wet nature were advised to drink wine in order to balance the humors (Hippocrates).

The Talmudic Era

The Jewish Talmud c. 400-600 CE contains extensive and wide ranging commentary on wine. The text is usually concerned regarding its suitability for ritual use but there is also discussion regarding wine’s health and medical benefits.

Wine as medicine is highly regarded in the Talmud, in fact the Babylonian edition (Talmud Bavli ca. ~500 CE), states “…at the head of all healing am I, wine. In a place where there is no wine, herbs are required there as medicines” (Bava Batra 58b). Some wines were diluted with water, while others included cinnamon, capers, long pepper, vinegar, salt, and seawater to improve the taste, act as a preservative or for medicinal benefit. For example Aluntit is old wine, mixed with water and balsam (Avodah Zarah 30A) taken to cool down after going to the bathhouse. Intestinal pain was treated by drinking wine with long peppers, impotence with wine and saffron, roundworms were cured by drinking wine with a laurel leaf, and illness of the spleen was treated with dried leeches in wine (Gittin 69b).

The Medieval Era

There are multiple medical authorities throughout the medieval and renaissance that recommended spiced wines for various illnesses and injuries.

Hildegard von Bingen

Hildegard von Bingen (1088-1179), was a German Benedictine abbess and a renaissance women before anyone had heard of the renaissance. Among her many accomplishments, Hildegard was a mystic, a composer, philosopher, and author of theological, botanical, and medical texts. Hildegard codified her medical theories and practices in two books, Physica and Causae et Curae. Physica describes the scientific and medicinal properties of various plants, stones, fish, reptiles, and animals. Physica also contains what may be the first description of hops as a preservative for beer.

The second text, Causae et Curae primarily reviews the human body and it’s physiology. The text includes details on women’s health and the specific origins and treatment of disease to include influences such as the lunar cycle (Healthy). For example she compounds a solution made from violet, rose and fennel tincture added to wine as a treatment for eye ailments, advises chewing fresh lettuce or chervil mixed with wine to treat periodontal disease and treats toothache with absinthe (wormwood), verbena cooked in wine and sweetened with sugar (Sweet, pg 392).

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon, (~1220-1292) in The Cure of Old Age and Preservation of Youth (Bacon, 1683 Translation) he recommends wine to cheer the heart (pg 104), improve circulation (pg 112), and with Celtick Spike (Valeriana celtica ) to keep the “Breast and Lungs clean” (pg 97). He advises wine boiled with pepper, ginger, cloves, and saffron to make the blood clear and fine (pg 128). Although not sweetened, these spices are similar to those in hippocras.

John of Gaddesden

John of Gaddesden (~1280-1361) an English theologian, physician, one of the most celebrated medical authorities of his day, wrote the treatise Rosa Medicinæ in which he recommends wine soaked bandages and hot wine as a disinfectant (Chomley pgs 37, 58, 64).

Hieronymus Brunschwig

Hieronymus Brunschwig (1450 – 1512?) an Alsatian military surgeon, alchemist and botanist, advocated a mixture of strong Gascony wine, brandy and herbs known as aqua vitae composite to nourish the blood, cleanse wounds, treat palsy, ringworm, expel poison and overall help the heart, stomach and liver (Sandler pg 16).

Valerius Cordus

Valerius Cordus (1515- 1544) a German physician and botanist author of one of the greatest pharmacopoeias and herbals in history, used wine with some very odd ingredients including scorpion and centipede ashes, and wolf’s liver. I’m not sure what he was treating.

Paracelsus

Phillip von Hohenheim aka Paracelsus (~1493-1541) was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance (Britannica). Paracelsus famously stated, “Whether wine is a nourishment, medicine or poison is a matter of dosage”. He made extensive use of Laudanum which amongst other ingredients contained opium dissolved in alcohol. Another remedy was Vinum Ferri, iron wine which may have also contained antimony. Paracelsus did not invent iron wine. In 1241, King Henry III was presented with 3 tuns of ferratum wine by the Cluniac Prior of Ogbourne St. George (Seward pg129). Formulae for vinum ferri are found in pharmacopeia into the late 1800s and of course oral and parenteral iron supplements remain part of modern medicine (Sandler, Schwarcz). In sixteenth century Italy, hospitals were well stocked with wine. This was not an indulgence buy rather a liquid pharmacy where wines were selected as treatment according to humoral theory (Varriano pg 129).

A Few Other Medieval References

During this same time period, people continued to enjoy spiced wine as a luxury, a medicinal, and a digestive. Piment (pimen, pyment) a spiced, sweetened wine similar to hippocras is mentioned in medieval Occitan literature. Its name derives from the Late Latin pigmenta “vegetable juice” in turn is derived from the Latin pigmentum, “pigment”. This is possibly because the spices added color to the beverage (Piment). Over time the term piment seems to have fallen out of favor and merged with hippocras. Modern usage defines piment as mead made with grapes or grape juice (BJCP).

Piment, like hippocras was considered to have medicinal properties. Arnald de Vilanova (1240-1311) a Catalan theologian, alchemist, philosopher, physician and the reputed author of Regiment de Sanitat (Rules of Health) advises its use for various conditions. He recommends honey mixed with pounded chervil and steeped in wine as treatment for cancer, wine mixed with pennyroyal to treat jaundice and as a soak for arthritis. Arnald recommend the addition of sugar to his formulae for wormwood wine, hyssop wine, and anise wine to increase their potency(de Villa Nova).

Piment is offered to Percival in Chrétien de Troyes’ (1130-1190 CE) Perceval, the Story of the Grail (de Troyes, Clark). Pyment and ypocrase are mentioned in the ca. 1475 poem The Squire of Low Degree (Kooper, lines 754, 758, 760), The Romance of Sir Beues of Hamtoun c. 1300 (Wharton 178), (Herzman, Kolbing) and Chaucer’s The Millers Tale line 3378.

Sugar and Spice

Some of the more common spices used in hippocras included ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, pepper and grains of paradise. These spices were all considered to be warming, strengthening of the stomach and good for digestion.

During the medieval period and earlier, sugar was considered a spice and a medicinal. The Greek physician Dioscorides in the 1st century AD wrote “There is a kind of coalesced honey called sugar found in reeds in India and Arabia …similar in consistency to salt and brittle [enough] to be broken between the teeth like salt. It is good dissolved in water for the intestines and stomach.” (Dioscorides, book ii, pg. 226-227). St Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) an Italian Dominican friar was one of the most influential medieval thinkers. Discussing whether sweets broke a religious fast, he stated “Though nutritious in themselves, sugared spices are nonetheless not eaten with the end in mind of nourishment, but rather for easing digestion. Accordingly, they do not break the fast any more than the taking of any other medicine” *(Mintz pg 99). The physician and scholar Constantinus Africanus (1020-1087 ) prescribed sugar for cough, and stomach disease, the byzantine emperor Manuel Comnenus (1143-1180 ) recommended it for fevers and Albertus Magnus (1200-1280 ) noted its humoral properties to be warm and moist and so good for the stomach*(Goldstein pg 671).

Overtime, especially with increased access to cheaper imported sugar, it became a luxury ingredient in general use though it never fully shed its medicinal origins. The 1474 cookbook, De honesta voluptate et valetudine (“On honorable pleasure and health” (the first printed cookbook), by Bartolomeo Sacchi better known as Platina included recipes using up to half a pound of sugar (Schmidt). Bartolomeo Scappi’s 1570 cookbook Opera di Bartolomeo Scappi includes many dishes which are distinctly sweet, some even calling for a pound of sugar. (Scappi, Scully pg 585 ). , It is interesting that many of these sugared recipes are included in the chapter on dishes for the sick. This would reinforce the medicinal nature of sugar.

* NB: I have had a difficult time finding the original sources.

The Banquet and Voideé: The evolution from medicine to luxury

The medieval feast began with a course called entrée de table (“entering to/of the table”) and ended with the issue de table “exiting the table” (Jurafsky). It was at the end that hippocras was typically served, although some menus include it as part of the appetizer too. Of note the term banquet, originally designated a separate course consisting of wines, ipocras, and sweets served at the end of the meal. Frequently, the banquet would be served in a separate location enabling the main hall to be cleared or “voided’, thus the term void (Fitzpatrick, pgs 5, 107).

A course of sweets similar to a voideé might be offered to guests or simply taken by the individual at night in their chambers. For example, in 1472, Lord Gruthuyse, a Burgundian nobleman on a special mission from Charles Duke of Burgundy to Edward the Fourth stayed the night at Windsor Castle. Following a banquet given by the Queen:

“And when the Kinge and the Quene, with all her ladyes and gentlewemen, had shewed hym these chambres, they turned againe to theire owen chambres, and lefte the sayde Lorde Grauthuse there, accompanied with my Lorde Chamberlein, whiche dispoyled hym, and wente bothe together to the Bayne . . . And when they had ben in theire Baynes as longe as was there pleasour, they had grene gynger, diuers cyryppes, comfyttes, and ipocras, and then they wente to bedde.” (Rye pg xliii)

Recipes are found in the 13th century French Tractatus de Modo, and the Italian Liber de Coquina, the 14th century Catalan cookbook The Book of Sent Sovi , the Forme of Cury from England, the French Ménagier de Paris and the 15th century Boke of Nurture (c ~1440) by John Russell (“Early Medieval…). Several menus in Le ménagier de paris (c. 1390) end with hippocras and wafers (Hinson), while a recipe for ipocras in The Booke of Kervynge (c. 1508), finishes with the statement “serve your soverayne with wafers and Ipocras” (de Worde). There are references as well to pyment and wafers in The Sent Sovi, the Roman de Flammenca (1240) and Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale lines 270-271. In the 1520 Catalan cookbook Libre del coch the recipe is given as pimentes de clareya. Interestingly, in The Boke of Nurture there are different recipes for the wealthy as well as for the common people. For common folk, the recipe is simpler “commyñ peple / Gynger, Canelle / longe pepur / hony aftur claryfiynge,” (line 124).

The Boke of Nurture presumes ypocras is taken at the end of a meal or before retiring. Interestingly it also glosses ypocras and pyment as spiced sweetened wines. For example at night “but ȝiff he haue aftur, hard chese / wafurs, with wyne ypocrate, ” (line 84), or as part of the last course of a multi-course dinner “ Withe Gyngre columbyne, mynsed manerly, Wafurs with ypocras” (lines 758-759), and “serue hit forth with wafurs boþe in chamber & Celle”. In the section laying out an elaborate dinner menu it is served with wafers, white apples and caraways towards the end of the final course (lines714-715). Russell mentions using Turnsole (Chrozophora tinctori or Heliotropium) to help color the hippocras red “Turnesole is good & holsom for red wyne colowrynge” line 173. Unfortunately, Heliotrope can be hepatotoxic in large quantities. All this reinforces the virtual interchangeability of the two beverages as well as its placement at the end of a meal and at night. It is not clear how it differentiates between the two beverages, although it is possible that it considers hippocras a type of piment (Russel).

Hall, in The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancastre and Yorke, (published 1548, the year after his death), makes several comments on the timing of the void and ipocras:

” But to returne to thende of this honorable feast, the tables auoyded, the wafers were brought. Then Sir Stephen Ienys, that tyme Maior of London, whom, the kyng before he satte doune to dynner, had dubbed knight, whiche, beganne the Erles Table that daie, a rose from the place where he satte, to serue the Kyng with Ipocras, in a Cuppe of Golde,”

“ within a litle season was brought to the quene with a solempne seruice in great standyng spyce plates, a voyde of Spice and subtilties with Ipocras and other wynes.” “and when they had daunced, then came in a costly bāket and a voidy of spi∣ces, and so departed to their lodgyng.” After this pastyme ended, the kyng and the Ambassadours were ser∣ued at a bancket* with .ii.C. & .lx. dyshes: & after that a voydee of spyces.” After the twoo kynges had ended the banket, and spice and wyne ge∣uen to the Frenchemen, Ipocras was chief drinke of plentie, to all that would drinke” (Hall).

At Queen Elizabeth‘s coronation in 1559, as recorded by Raphael Holinshed in The firste [laste] volume of the chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande:

“And after thys, The L. Ma […] of London serueth the Queene of Ipocrasse. at the seruing vp of the Wafers, the Lorde Maior of London went to the Cupboord, and fitting a cup of golde with Ipocrasse, bare it to the Queene..” (Holinshed).

Conclusion

Throughout history spiced wine has been a medicinal, a digestive, and a luxury. It seems to have been all things to all people in all places and in all times. They have been used to entice lovers, honor guests, dress wounds, to fortify ones strength, aid digestion, and cure an innumerable number of ailments. Of course, as with many things, changes in taste and the increased popularity of distilled beverages slowly led to the decline in hippocras’ popularity. Digestifs however remain popular in the form of various liquors and even after dinner wines, liquors, and brandies. Hippocras is easily made and I heartily recommend you try one of the many SCA period recipes available. Here follow two recipes for your enjoyment.

Appendix: Two Early English Recepies

1) The first English recipe for ypocras is found in the Forme of Cury c. 1390. It is actually a recipe for hippocras powder and does not specify how much wine and sugar to use.

“Pur fait Ypocras.

Treys Unces de canell. Et iij unces de gyngener. spykenard de Spayn le pays dun deneres. garyngale. clowes, gylofre. poivr long, noiez mugadez. maziozame cardemonij de chescun i.qrt douce grayne [?] de paradys flour de queynel de chescun dimid unce de toutes. soit fait powdour and serve it forth.”

Modern Redaction: To make hippocras: Take three ounces of cinnamon and three ounces of ginger. One denier (a French penny) worth of spikenard of Spain. Galangal, cloves, long pepper and nutmeg, marjoram and cardamom, a quarter ounce for each. Grains of paradise and cinnamon flower (cinnamon flower buds are available), a tenth ounce for each. So make the powder and use it.

Presumably, the cook already knows to mix the hippocras powder with wine and sugar although this is not specified. A second recipe in the text, Potus ypocras notes “Si deficiat sugir, take a potel of hony” if you don’t have sugar use honey.

2) A more complete recipe from A Noble Book of Festes Royalle and Cokery (London: 1500).

Take of chosen Cinnamon two ounces, of fine ginger one ounce, of graines half an ounce, bruise them all. Steep them in three or four pints of good odiferous wine, with a pound of sugar for 24 hours. Then put them into a woolen Ipocras bag and so receive the liquor. The readiest and best way is to put the spices with the half pound of sugar and the wine into a stone bottle, or a stone pot stopped close, and after twenty four hours it will be ready, then cast a thin linen cloth, and a piece of a boulter cloth in the mouth, & let so much run through as you will occupy at once, and keep the vessel close, for it will so well keep both the sprite, odour, and vertue of the wine, and also spices.

Modern redaction: Bruise two ounces of cinnamon, one ounce ginger, and a half-ounce of grains of paradise. Steep the spices and sugar in one 750ml bottle of wine for 24 hours, strain and serve.

References

Apicius. (ed, Thayer, Bill) De Re Coquinaria of Apicius. University of Chicago. 29 September 2013. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Apicius/1*.html

Bacon, Roger, Browne, Richard (Trans.) . The cure of old age and preservation of youth, by Roger Bacon, a Franciscan frier. Translated out of Latin, with annotations and an account of his life and writings by Richard Browne. Also, A physical account of the tree of life, by Edw. Madeira Arrais Translated out of Latin; with Annotations, and an Account of his Life and Writings. L. Coll. Med. London. 1683

Baker, Moses N. (1981). The Quest for Pure Water: the History of Water Purification from the Earliest Records to the Twentieth Century. 2nd Edition. Vol. 1. Denver, Co.: American Water Works Association

BJCP. Pyment. © 1999-2020, Beer Judge Certification Program. http://www.bjcp.org/style/2015/M2/M2B/pyment/

Britannica. Song of Songs. Encyclopedia Britannica 19 Sept 2013. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Song-of-Solomon

Britannica. Ebers papyrus. Encyclopedia Britannica. 7 August 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ebers-papyrus

Bryan, Cyril P. Trans. The Papyrus Ebers. Ares Publishers, Inc. Chicago 1974. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/ptid=coo.31924073200077&view=1up&seq=5

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. 1387

Chomley, H.P. John of Gaddesden and the Rosa Medicinae. 1912. Forgotten Books Dec 2017

Clark, J. Chretien de Troyes. Perceval, or the Story of the Grail. Web 12 December 2017. http://clark.bengalenglish.org/wpcontent/uploads/2011/08/Perceval_and_the_Holy_Grail_Passage.pdf

Crowley, Theodore. Roger Bacon, English philosopher and scientist. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roger-Bacon. Accessed 25 June 2020

Day, Ivan. More on Hippocras. Historic Food. Ivan Day 1977. Web 1 Sept 2016. http://historicfood.com/Hippocras%20Recipes.htm

de Troyes, Chrétien. Perceval, the Story of the Grail https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/French/DeTroyesPercevalPartIII.php

de Worde, Wynken. Boke of keruynge. London, 1508. Royal Library. University of Cambridge. http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/PRSEL00005-00019/1

Dioscorides. Materia Medica. http://www.cancerlynx.com/BOOKTWO.PDF

Fitzpatrick, Joan. Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: Culinary Readings and Culinary Histories 1st Edition. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. 2010

Goldstein, Darra (ed). The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. Oxford University Press; 1 edition (May 1, 2015)

“H3196 – yayin – יַיִן – Strong’s Hebrew Lexicon (KJV).” Blue Letter Bible. Accessed 31 Jul, 2020. https://www.blueletterbible.org//lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=h3196&t=KJV”t=KJV

Healthy Hildegard. Causae et Curae. The Healthy Hildegard Community. https://www.healthyhildegard.com/causae-et-curae/

Herzman, Ronald B, ed. Bevis of Hampton. https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/salisbury-four-romances-of-england-bevis-of-hampton

Hinson, Janet (Trans), Pichon, Jerome. Le Menagier de Paris. 1393, from the 1846 edition http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Medieval/Cookbooks/Menagier/Menagier.html & http://www.gutenberg.org/files/44070/44070-h/44070-h.htm

Hippocras. Encyclopedia Britannica. 1911. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Hippocras

Hippocrates., Galen., Coxe, J. Redman. (1846). The Writings of Hippocrates and Galen. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston. https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/hippocrates-the-writings-of-hippocrates-and-galen/simple#lf0881_label_877

Wikipedia contributors, “History of sugar,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 31, 2020). https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_sugar&oldid=970263613

Holinshed, Raphael. The firste [laste] volume of the chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande conteyning the description and chronicles of England. 1571. http://tei.it.ox.ac.uk/tcp/Texts-HTML/free/A03/A03448.html

Hoolihan C. Wine and Regimen from Hippocrates to the Renaissance. Caduceus. 1993; 9(1):5-16. https://ia600504.us.archive.org/32/items/caduceushuman911993unse/caduceushuman911993unse.pdf

Jurafsky, Dan. The Language of Food. http://languageoffood.blogspot.com/2009/08/entree.html accessed 5 July 2020

Karaberopoulos, Demetrios, et al. The Theriac in Antiquity. The Lancet, Volume 379, Issue 9830, pgs 1942-1943, 26 May 2010. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)60846-0/fulltext

Klein, Ernest. רֶֽקַח Klein Dictionary. https://www.sefaria.org/Klein_Dictionary%2C_%D7%A8%D6%B6%D7%A7%D7%95%D6%B9%D7%A8%D6%B0%D7%93?lang=bi

Kolbing, Eugen ed. The Romance of Sir Beues of Hamtoun. https://archive.org/stream/romancesirbeues00klgoog/romancesirbeues00klgoog_djvu.txt:

Kooper, Erik, ed. The Squire of Low Degree. https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/kooper-sentimental-and-humorous-romances-squire-of-low-degree;

Latdict: Conditum, Condit. http://latin-dictionary.net/definition/12264/conditum-conditi

McGovern, P, Jalabadze, M, et al. Early Neolithic wine of Georgia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Nov 2017, 114 (48) E10309-E10318; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1714728114

McGovern, P. Archeological Oncology. 24 March 2010. Accessed 4 March 2020. https://www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/?page_id=496

McGovern, P, Zhang, J. et al. Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Dec 2004, 101 (51) 17593-17598; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0407921102

McGovern, P, Mirzoian, A. Hall, G. R. Ancient Egyptian herbal wines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences May 2009, 106 (18) 7361-7366; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0811578106

Mintz, Sidney W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Viking, 1985.

Nikolva, Piareta, et al. Wine as a Medicine in Ancient Times. Scripta Scientifica Pharmaceutica, 2018;5(2):14-21 Medical University of Varna, Bulgaria. November 2018. http://journals.mu-varna.bg/index.php/ssp/article/viewFile/5610/4986

“pigmentum” in WordSense.eu Online Dictionary (9 March 2020). https://www.wordsense.eu/pigmentum/

“Piment.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/piment. Accessed 9 March 2020

Pliny the Elder, Bostock, John, Ed. The Natural History. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/textdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3Ddedication & http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D14

The Rig Veda. Wikisource. Accessed 28 June 2020. https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.phptitle=The_Rig_Veda&oldid=10109237″oldid=10109237

Roos, Anna Marie Eleanor. Biomedicine and Health: Galen and Humoral Theory. 25 March 202. https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/science-magazines/biomedicine-and-health-galen-and-humoral-theory

Russell, John., Furnivall, Frederick J, (ed) . The Boke of Nurture c. ~1450Early English meals and manners: With some forewords on education in Early England, 1868. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/24790/24790-h/nurture.html

Rye, William Brenchley. England as Seen by Foreigners in the Days of Elizabeth & James the First: Comprising Translations of the Journals of the Two Dukes of Wirtemberg in 1592 and 1610; Both Illustrative of Shakespeare. United Kingdom: J. R. Smith, 1865.

https://ia802807.us.archive.org/11/items/englandasseenbyf00ryew/englandasseenbyf00ryew.pdf

Sandler, Merton; Pinder, Roger. Wine: A Scientific Exploration. Taylor and Francis, London, 2002

Scappi, Bartolomeo. Opera Di M. Bartolomeo. https://ia600209.us.archive.org/14/items/operavenetiascap00scap/operavenetiascap00scap.pdf

Scappi, Bartolomeo, Scully, Terence (Trans) The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570): L’arte et prudenza d’un maestro cuoco (The Art and Craft of a Master Cook) (Lorenzo Da Ponte Italian Library). University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division; 1 edition (January 22, 2011)

Schmidt, Stephen. What, Exactly, Was the Tudor and Stuart Banquet? August 2019. https://www.manuscriptcookbookssurvey.org/what-exactly-was-the-tudor-and-stuart-banquet/#fnref-3080-6 . Web Access June-July 2020

Schwarcz, Joe. Opium and laudanum history’s wonder drugs. July/August 2015 https://www.cheminst.ca/magazine/article/opium-and-laudanum-historys-wonder-dru

Seward, Desmond. Monks and Wine. Crown publishers. First American edition (October 1979)

Singer, P. N., Galen. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/galen & https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/galen/

Scully, Terrance. The Viander of Taillevent: An Edition of All Extant Manuscripts. University Of Ottawa Press, 1 Jan 1988 Pg 346

Sweet, Victoria. Hildegard of Bingen and the Greening of Medieval Medicine. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Fall 1999), pp. 381-403. The Johns Hopkins University Press

Varriano, John. Wine: A Cultural History. Reaktion Books (February 15, 2011)

von Klein, Carl H. The Medical Features of the Papyrus Ebers. Reprinted from The Journal of the American Medical Association. Chicago, 1905. https://archive.org/details/cu31924000900849/page/n3/mode/2up/search/wine

Ypocras. Illustration. https://www.historicfood.com/Ypocras.htm

One comment

Comments are closed.