Arts & Sciences Research Paper #13: Persian Plants in Miniature: What are the Plants in Persian Illuminations?

Our thirteenth A&S Research Paper comes to us from Lady Raziya bint Rusa, of the Barony of Carolingia. She examines a question that troubles many people working with illuminated manuscripts: what exactly are those plants in the illuminations? Are they fanciful or are they plants that really existed in history? (Prospective future contributors, please check out our original Call for Papers.)

Persian Plants in Miniature: What are the Plants in Persian Illuminations?

Four years ago I bought a book of Persian miniatures for reference to help me sew garb. As I paged through over breakfast one illustration caught my eye – a hollyhock. I am a gardener by trade, and thought it out of place that a hollyhock, a staple of the English country garden, would be found in Persia. To satisfy my curiosity I did a quick web-search into Persian Plants. This line of questioning would be the undoing of my motivation to sew; two years later I had a seven thousand entry horticultural database and no new garb.

Contents

Individual Plants from Miniatures

Bibliography

My early research led me to incomplete and unsatisfying websites that were rudimentary in their lists of Persian plants. Further digging led me to a promising link titled “Flora of Iran”. Two clicks into the eponymous site was a list of plants alphabetical by genus and species. The Flora of Iran (FOI) included family names and not much else; it had no common names or any other information on the plants. However the site did have thousands of entries including a boisterous thirty nine species in the Genus Alcea (hollyhock). I found many familiar names while reading, which I did with fascination. The list was large and complete looking; this was the sort of information I was looking for, this was worth digging into. Unfortunately I was hampered in using the data: this lovely list was a text document, not a spreadsheet. A couple months later I finished fixing that particular problem.

During the course of data entry I realized that I needed to verify that these plants were all native to the old world. I cross-referenced the data with several reputable sources that cover plant origins: Hortus Third, and the USDA Plant Database. I removed nineteen plants from my list. Species tend to travel from the old world to the new world, and not vice-versa. I am still ignorant of whether, and when, these plants may have been moved around the old world, since some of them certainly did not originate in Persia.

After winnowing my list slightly, I made a best attempt to identify the plants I was looking at in miniature. I scoured all the sources I had access to and I entered these plants into my database, noting which ones I was not certain of. I have looked at Ottoman Turkish miniatures as well, particularly those painted around the time of conquest over Persian territory. After this step I was left with another important issue: species familiar in cultivation such as fruit trees showed up in pictures but were not listed in the FOI. I realized the FOI only included species that were naturalized to Iran, not those in cultivation. I only had a list of those plants that grow themselves in the wild, native or introduced. I needed a list of domesticated plants.

A good friend of mine had been cooking recipes from Ibn Sayyar al-Warrāq’s “Annals of the Caliph’s Kitchens”. Good friends let you borrow al-Warrāq. This text is considered Baghdadi, not Persian, however later Persian cultures did include Baghdad, so it is a good source for information on plant use in the region. The book contains a few hundred references to specific plants which the translator calls out botanically. Meticulous chefs are of great benefit to horticulturalists. After adding these plants I had a list that was nearly complete. In more recent times I have been looking into information from medical texts, and Andalusian horticultural treatises to further complete the list.

After much pruning, the database currently contains 6964 plants. I have included: Genus, species, Family, common names, and some Arabic, Farsi, and Turkish names. I also determined whether or not the plant is available in the United States, and some basic notes on its use. I have made the information publicly available via my own site: https://sites.google.com/site/raziyasca/services/persian

However this still begs the question: What plants are found in the miniatures? I have found a number of plants that I can narrow down enough to put familiar names on. Each time I have discovered a recognizable plant, I check it against suspects in the database. The following plants are those which I have an educated guess as to their identity. (NB: Clicking on the name of each plant will take you to a modern photo of the plant, while clicking on each manuscript image will take you to a larger version.)

Plants from Miniatures

Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens)

It is difficult to identify many trees in Persian miniatures. There is a tendency for them to be drawn with the subtlety of a lollipop. Cypress is a tree which has a very dense columnar form. Because of references to it in nearby Andalusian texts, and its presence in modern Iran, I suspect it was well known to the Persians.

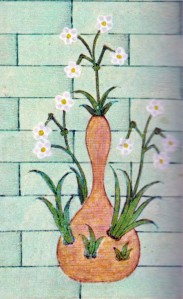

Daffodil (Narcissus tazetta)

Daffodil, otherwise known as Narcissus, is a species which is very clear in illustrations. While many species of Narcissus are currently in cultivation, and certainly may have been grown in Persia, N. tazetta is the only species listed as currently naturalized in Iran. In modern times this species is also grown in a pure white form and called a “paperwhite”. (Note that there is also another species called paperwhite, N. papyraceus.) N. tazetta are often found for sale around the holiday season. It is interesting that it is also grown in a container in period.

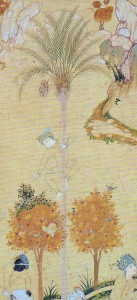

Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera)

The date palm is an easy identification. Many illustrations in period are rudimentary, but one jumped out at me in its clarity. While the miniature is not finished being painted, it shows the fruit and fronds with good detail. Fruits and flowers form the core of how most plant classification has been done in the past. Modern research into genomes have clarified previous taxonomy, but flowers and seeds still form the basis of hands-on identification.

Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva)

Daylilies are a familiar face in modern gardens and were imported from the old world to North America. The old orange varieties that grow along Maine ditches grew in ancient Persia.

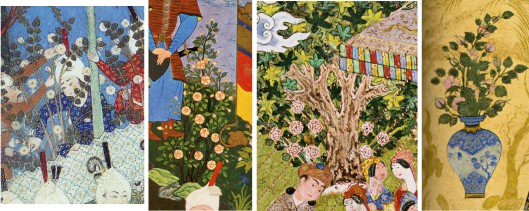

Fruit Trees (Rosaceae)

Almond (Amygdalus), Apple (Malus), Cherry (Cerasus), Hawthorn (Crataegus), Pear (Pyrus), Plum (Prunus)

There are a number of flowering trees pictured in Persian miniatures, all of which I can only narrow to the family. They all have five petals and are colored: white, pink, red, or a combination. For those familiar in identifying trees in the Rosaceae family, there are critical differences in the time of bloom, the structure of the tree, and the size and shape of the leaf. The structure of the trees and the leaves are stylized to the point where it is impossible to tell if a difference is for accuracy or aesthetics. One also quickly notices that in Persian miniatures, ALL plants are in bloom at the same time, which is obviously erroneous even to a casual viewer.

Hollyhock and others (Malvaceae)

Hibiscus (Hibiscus), Hollyhock (Alcea), Mallow (Althaea, Malva), Tree Mallow (Lavatera)

Hollyhocks started me on this journey, but are another group difficult to pinpoint. The mallow family (Malvacaea) corresponds well to the general depiction: five petaled flowers born on long stems amid five lobed leaves, flowers are usually two-toned: red, white, or pink. Based on the large number of species listed in the FOI in each of these Genera, it is likely that all of these are native to Persia, and they have spent millennia evolving into different species. Pictured is the traditional hollyhock; it is not in the FOI list but that exclusion does not exclude it from being a species cultivated in Persia.

Iris (Iris spp.)

Iris is easily identified, and is likely Iris germanica or I. kashmiriana. While not all illustrations match, seen here is a common depiction of: two-tone color, yellow bearding, and wide leaves.

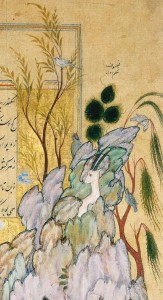

Oak (Quercus spp.)

It is difficult to notice oaks in miniatures if one is only familiar with the pointed lobes of red and black oaks. While I cannot confirm the pictures are in fact oak, I think it is very likely. These trees can have a variety of leaf shapes including rounded lobes. Pictured here is Quercus robur, English oak.

Plane Tree (Platanus orientalis)

Plane tree, or sycamore, is a river species known for its peeling bark. As the bark peels, it reveals a light under layer as it peels off the tree. It has deeply lobed leaves, much like a maple. Due to variety in some illustrations, Maple-like leaves with brown bark, or white bark and non-lobed leaves I was unsure as to the identity of this tree for a time. Fortunately in one of the periods of more meticulous scribal work I found a specimen in fruit. The fruits of the plane tree are distinctive burr-like balls that hang from a stem. In period this tree is often pictured growing on the edge or a river or stream.

Pomegranate (Punica granatum)

Pomegranate can be hard to tell from other fruit trees. Many fruit trees are only shown as having round fruit of either red, yellow, or orange in color. Pomegranate stands out because of the sepals which stick out of the end of the fruit.

Poplar (Populus spp.)

While these trees look superficially like birch, birch is not a Persian genus. Instead these are poplar. P. alba and P. caspica have the characteristic white bark, a similar shape of leaf.

Poppy (Papaver spp.)

There are too many poppies to guess which species is pictured; photographed is P. orientale, a common garden variety. Most species in the FOI have the characteristic reddish-orange petals and black “eyes”.

Reed (Arundo donax or Phragmities australis)

Pictured is a plant easily identified as a large reed. It is shown both growing on the edge of water and much larger than surrounding objects. Arundo and Phragmites are similar enough that I cannot differentiate between the two in miniature.

Rose (Rosa spp.)

(Rosa damascena, Rosa canina, Rosa spinosissima, Rosa centifolia)

Roses are quite possibly one of the most canonically Persian flowers. Unlike many of the other plants, roses are not shown pictured consistently. I have included four unique depictions of roses. It is interesting that while other plants were copied or traced, the scribes took time to illustrate roses anew each time. Some roses have a simple 5 petaled form, others seem to have double petals, and some have a form with more than double. This diversity suggests that a variety of different rose types were being grown in period.

Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus)

Rose of Sharon is the weakest illustration that I have found; it is a stretch to identify this as the plant in question. I hypothesized that it was not a rose because despite having five petals the illustration has two-tone color to the petals. The plant pictured is woody not herbaceous, which rules out Malvacaea.

Tulip (Tulipa spp.)

While we associate tulips with Holland, they were originally a species found in the Mediterranean, the Middle-East, and Central Asia. They are very happy in a much drier climate than what we typically raise them. Due to the plethora of species found in the FOI, I am unsure as to species: many look very similar. Several species have colors like those in the miniatures. Pictured is T. linifolia.

Willow (Salix babylonica)

Willows are seen in two basic forms in the miniatures: upright and weeping. This suggests at least two separate species. Pictured is a weeping species.

Back to Top

Bibliography

Al-Muzzafar ibn Nasr Ibn Sayyar al-Waraq. 2007. Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens: Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s Tenth Century Baghdadi Cookbook. Trans. Nawal Nasrallah. Boston: Brill.

Atil, Esin. 1987. The Age of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Baily, Liberty Hyde, and Ethel Zoe Bailey. 1976. Hortus Third: A Concise Dictionary of Plants Cultivated in the United States and Canada. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Canby, Sheila, R. 1993. Persian Painting. Northampton Massachussetts: Interlink Books.

Canby, Sheila, R. 1999. The Golden Age of Persian Art 1501-1722. London: The British Museum.

Chelkowski, Peter J. 1975. Mirror of the Invisible World: Tales from the Khamseh of Nizami. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Conan, Michael. 2007. Middle East Garden Traditions: Unity and Diversity. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

Hagedorn, Annette, Norbert Wolf. 2009. Islamic Art. Germany: Taschen.

“Plant Families” in Flora of Iran [database online]. [cited May 8, 2013].

“Plant Finder” in Missouri Botanical Garden. [database online]. [cited May 24, 2013].

Robinson, B.W. 1991. Fiftteenth-Century Persian Painting Problems and Issues. New York: New York University Press.

Soudavar, Abolala. 1992. Art of the Persian Courts: Selections from the Art and History Trust Collection. New York: Rizzoli.

Swietochowski, Marie Lukens, and Stefano Carboni, with essays by A. H. Morton and Tomoko Masuya. 1994. Illustrated Poetry and Epic Images: Persian Painting of the 1330s and 1340s. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Titley, Norah M. 1983. Persian Miniature Painting and its influence on the art of Turkey and India. Austin: University of Texas Press.

USDA Plant Database [database online]. [cited May 8, 2013].

Welch, Stuart Cary. 1972. A King’s Book of Kings: The Shah-Nameh of Shah Tahsmasp. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wikipedia [database online]. [cited May 8, 2013].