A&S Research Paper #1. ‘A smoke of cameryke, wrought with blake worke’: An overview of monochromatic embroidery in Early Modern England during the reign of Elizabeth I

Greetings, and welcome to the East Kingdom Gazette’s new feature: A&S Research Papers! Our first article comes to us from Mistress Amy Webbe, of the Shire of Barren Sands, who is presenting her article on monochromatic embroidery. The paper was presented initially to the East Kingdom Embroiderer’s Guild, the Keepers of Athena’s Thimble. Thank you, Mistress Amy, for starting off the new feature so well! (Prospective future contributors, please check out our original Call for Papers.)

‘A smoke of cameryke, wrought with blake worke’: An overview of monochromatic embroidery in Early Modern England during the reign of Elizabeth I

A woman’s coif, circa 1600, accession number 1996.51. Image from the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A woman’s coif, circa 1600, accession number 1996.51. Image from the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Abstract: Monochromatic embroidery in counted forms was prevalent throughout the medieval Islamic world. Subsequent contact with southern European cultures introduced this form into mainland Europe, where it spread throughout Christendom. The arrival of the Reformation in England 1534, and the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558 allowed this art form to develop in uniquely English ways, establishing a unique aesthetic specific to the time and place. This paper will examine the aesthetics and techniques of monochromatic embroidery during the 16th century, focusing primarily on England, where this style of embroidery enjoyed its heyday.

Table of Contents

1. Historical Overview of Monochrome Embroidery

2. Aesthetics of Elizabethan Monochromatic Embroidery

3. Conclusion

4. Appendix: Extant Monochromatic Pieces Personally Examined by the Author

5. References

Historical Overview of Monochrome Embroidery

Monochrome embroidery, that is, embroidery using only one color of thread, is likely to be as old as needlework itself. It is easy to imagine our ancestors with leftover dye, and using it on a bit of thread that could then be used on an undyed garment, embellishing their clothing with something small. In “the Old World”, the earliest extant pieces that feature this sort of singlecolored thread, on an undyed or white ground, are found in what was considered “the Islamic World”. Islamic tradition cautions against the representation of living things, believing the power to create life is unique to God. Islamic embroidery, therefore, is often restricted to geometric patterns, and these are sometimes worked in a single color, and in double running or pattern darning stitches, such as fragment EA1984.168 at the Ashmolean Museum.  Fragment of an embroidered Islamic textile, Mamluk period (1250-1517), accession number EA1984.168. Image from the collections of the Ashmolean Museum.

Fragment of an embroidered Islamic textile, Mamluk period (1250-1517), accession number EA1984.168. Image from the collections of the Ashmolean Museum.

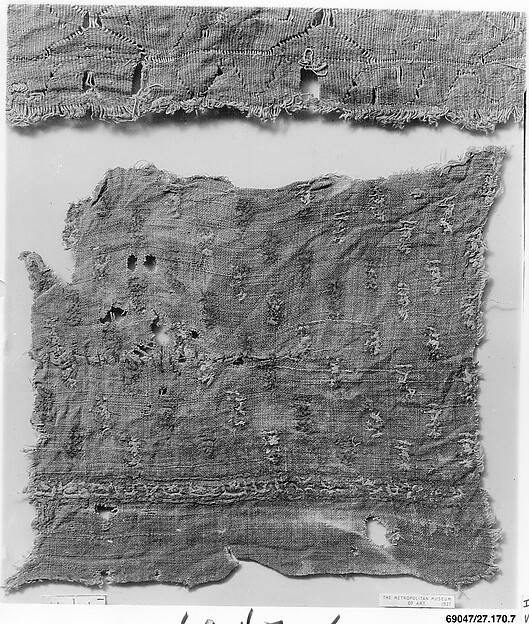

Textile fragment 27.168.8 from the Metropolitan Museum of Art contains some simple stepped and geometric figures that closely resemble what we may identify as “modern” blackwork.  Fragment of an embroidered Islamic textile, 13th or 14th century, accession number 27.168.8. Image from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fragment of an embroidered Islamic textile, 13th or 14th century, accession number 27.168.8. Image from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In contrast, extant European embroidery of the same time period is frequently ecclesiastical in nature, depicting many religious icons and figures, and polychromatic. What survives from prior to the Renaissance is a collection of altar cloths, copes, chasubles, miters—all items that would have been used and preserved in churches. English embroidery in particular had a famous period of embroidery, known throughout Europe as “Opus Angelicanum”, or “English Work”. This was characterized by the skillful use of color and shading, used particularly to denote people.

Monochromatic embroidery in Europe is mainly unknown from extant examples at this point in time, although a passage from Chaucer is frequently cited to show evidence of a history of English “blackwork”. A common translation reads:

Her smock was white and embroidered on the collar, inside and outside, in front and in back, with coalblack silk; and of the same black silk were the strings of her white hood, and she wore a broad band of silk, wrapped high about her hair. (NeCastro, 2011.)

However, this raises more questions than it answers. It has been posited that this statement is “proof” of a history of regular monochrome work existing in England prior to the 16th century, but one must ask the following questions with regards to the Chaucer reference: Are there pictorial examples or extant pieces to coincide with this reference? Is a 14th century smock of the same construction as a 16th, with a separate collar? What would the “collar” of the smock refer to? Are the “strings” on her hood perhaps ribbon, and the decoration on her “smock” ribbon as well? An alternate translation from the Liberius.org site reads:

White was her smock, embroidered all before/And even behind, her collar round about,/Of Coalblack silk, on both sides, in and out;/The strings of the white cap upon her head/Were, like her collar, black silk worked with thread.

This gives a slightly different interpretation, that may seem more plausible—that of these garments being made of black silk that was then embroidered. This also fits with the characterization of the Miller’s Wife as being a creature of fantastic taste and conspicuous consumption.

The end of the feudal system in Europe allowed workers to have more time and more money; workers could specialize in trades, and it is likely that this, combined with a more earthly focus after the Black Death, created an environment in which personal decoration was more accepted. The introduction of printed papers also meant patterns and images could be shared and traded, and this may also have contributed to a development of the culture of embroidery, particularly in the area of black on white embroidery, which may be an attempt to mimic woodcut illustrations. The influence of the Reformation also likely played a part, which we will consider later.

Although popular history holds that Catherine of Aragon brought the fashion for “blackwork” with her from Spain, there are no known extant pieces said to be the work of Catherine herself, and even her portraiture does not reflect this embroidery in great quantities. Some Spanish portraits hint at a bit of black decoration around the neckline, but this is not definitive, due to a lack of extant examples. Also, pieces housed in Spanish museums are frequently labeled as being of Italian origin. It seems as equally likely that Italian contact with the Islamic world may have been the connection, as many existing pieces share characteristics with each other, regardless of provenance. This may be expected under the universality of “Christendom”, as headed by the Pope in Rome. Henry VIII himself was even named a defender of the faith, a “fidei defensor”, by Pope Leo X, in 1521, and one could argue that this relationship accounts for the apparent similarities between European pieces in the first half of the 16th century.

A note on black dye: Prior to the discovery of the “New World”, black dye was often obtained from oak galls, which contained large quantities of tannin. However, this dye was extremely acidic, and would often eat away at fibers; many of the extant pieces we have today from England have disintegrating black silk needlework due to the dye being used. This was well known, and the Doge of Venice even went so far as to ban their use on wool fabrics. (Smith, 2009). This problem was solved somewhat by using a “provisional” natural dye as the base—first woad, then indigo, and later logwood. Logwood was under Spanish control as an import from the New World, and this may account for the reports of the higher quality of Spanish silk being much desired.

Beginning in the 16th century, we begin to see monochromatic embroidery represented in art. The paintings of Hans Holbein contains several images that seem to reference a geometric, “pixelated” style of embroidery. The Hans Holbein painting Darmstadt Madonna features a figure wearing a dress that many would argue reflects monochrome embroidery done in a simple linear stitch. And indeed, it does certainly appear to be so. However, almost no extant pieces exist from Germany at this time, so one cannot state that unequivocally, no matter how talented we presume the artist. Paintings of Jane Seymour done by him and attributed to his workshop show at least two different styles of what appear to be embroidered ruffles, although only one really represents this strictly geometric style. The archaeological record only minimally reflects this: Smock 2003.76 at Platt Hall of the Manchester City Galleries, dating from the mid 16thcentury England, does use what appears to be a double running stitch for the border of its neckline and down the sleeves, but this is supplemented by use of detached buttonhole embroidery. Shirt T. 112-1972 at the Victoria and Albert Museum also uses geometric styles and seems to imitate the styles common in Italian fashion of the time.  Embroidered English man’s shirt, ca. 1560, museum number T.112-1972. Image from the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Embroidered English man’s shirt, ca. 1560, museum number T.112-1972. Image from the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

A portrait of a young Mary I by Master John hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in London features what appears to be geometric red embroidery on the white linen clothing.  Portrait of Mary I, 1544, Item NPG 428 in the Primary Collection. Image from the collections of the National Portrait Gallery.

Portrait of Mary I, 1544, Item NPG 428 in the Primary Collection. Image from the collections of the National Portrait Gallery.

German modelbuchs from the time also feature geometric borders, that seem to be similar to painted examples.

It goes without saying that all art is influenced by the culture around it, and as that culture changes, so does the art reflect that change. Embroidery is no different, and following Henry’s break with Rome in the 1530s, we begin to see an “Anglicanization” of culture. Art and architecture both simplify. This is immediately obvious with the iconoclasm of the Churches; although the Church of England retained some simplified versions of ornament. Gone are the embroidered chasubles of the Bishops; in its place are simple white garments. The effort embroiderers may have spent glorifying the church now is spent glorifying themselves, and by the end of Elizabeth’s first decade of rule, in 1568, many aesthetics are becoming unique to the island, continually shunning anything Popish, be it embroidery, or Princes. As the reign continues, increased sumptuary laws sought to control the appearance of luxury, influenced, no doubt, by the Puritan element and their disdain of the sin of “pride” (Kirtio, 2012). This contrasts with embroidery on the Continent, which retains many of the geometric influences, and even expands into additional forms of counted embroidery, such as voided work.

So what, then, does this monochrome embroidery created during the reign of Elizabeth I look like?

Return to Table of Contents

Aesthetics of Elizabethan Monochromatic Embroidery

In the simplest terms, the style of Elizabethan monochromatic embroidery reflects the flowers of the English countryside, and the animals in an English garden.

Many familiar flowers and fruits are represented. One can find roses; pansies and violas; pea pods; strawberries; pears; grapes; gillyflowers (carnations); cornflowers; borage; honeysuckle; foxgloves; columbines; lilies; pomegranates. The skill of the embroiderer, however, does mean that some motifs are more challenging than others to decipher. Additionally, all manner of small animal can be found peeking out amongst the leaves of the embroidery, and even some more fanciful creatures have been depicted. One can spot bees; worms/caterpillars; fish; birds; butterflies and dragonflies; small mammals and household pets; and even the occasional phoenix or tiger.

The fascination with the natural world, be it flowers, insects and all manner of mammal and bird, is prominently displayed in most of these pieces. Many of the flowers featured would have been commonly found in the Elizabethan household’s kitchen garden, and it is easy to see that inspiration for many of the floral motifs used in these embroideries could have easily been found by looking out the kitchen window; however, images would also have been widely found in modelbuchs and “herbals”, such as Thomas Trevelyon’s “Miscellany”, which offered pictures of more exotic plants and animals, both old world and new.

In general, monochromatic embroidery during the reign of Elizabeth I, and continuing under James I, can be classified into several design “families”, based on final presentation: curved vines; lozenge patterns, diapered, and bands. It is important to recognize that many of these embroiderers were working “in a vacuum” in a sense. They would see what was becoming popular and fashionable, and replicate it as best they can. It seems unlikely they would have been engaging in a systematic study of the proper execution of these items—they would have been mimicking the styles within the limitations of their own skill and knowledge. (Please note the term limitation is used only in the sense of a narrow field of focus, and not as a disparagement of skill or execution.) The artistic expression of each embroiderer must also be taken into consideration—each individual will have a skill level and preference that is unique, and this must be considered when attempting to “classify” styles of monochrome embroidery. In the absence of widespread print or digital media, each embroiderer would need to determine for herself the best way for her to communicate the style.

Curving bands are some of the common layouts, and often this vinework is done in a metal thread, which contrasts nicely with the black embroidery, but one can easily find examples of curving vinework done only in the same black thread, although often with more elaborate stitching. It is interesting to note that these appear to be worked in two ways: in some extant pieces, it is very easy to see that the motifs were drawn on first, and the vines worked around them; on others, the regularity of the vines seems to suggest they formed the outline of the embroidery, and motifs added later. These curving designs usually terminate in a single flower or group of flowers; animal motifs are interspersed among the curves, and designs are often supplemented with little curlicues coming off of the main vine.

Lozenge designs are also quite common. This is when the embroidery is broken into a grid. As with the curving vines, this grid may be worked with either metal or silk threads. The motifs are then worked into the voids in the grid. This grid may leave rhombus and diamond shaped voids; hexagonal voids are seen in at least one example (Nightcap 198-1900 at the Victoria and Albert Museum); and some are simply constructed on a squared grid. The void in the grid is filled with one image large image, often a flower, but occasionally a bird or mammal.

English nightcap, ca. 1600, accession number 198-1900. Image from the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Diapered items also appear quite regularly, with the term “diapered” referring to the pattern consisting of repeats of small, identical figures. These repeats can be of one single design repeating, or a pattern of designs repeating. For instance, Coif and Forehead cloth 2003.63/2 at Platt Hall shows a simple flower and leaf design that is executed precisely throughout both pieces. In contrast, Coif and Forehead cloth 2003.64/2, also at Platt Hall, feature a more elaborate repeat—a three-armed strawberry bush with gold metal thread cinquefoils is alternated with small bees, also enhanced with metal thread. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust has an even more fanciful coif that features stylized fish interspersed with crescent moons. Several of the embroidered jackets we have are done in this diapered style, although at least one, at the Bath Fashion Museum, could be argued to have a lozenge design (1.03.137).

Bands are stripes of design that run at least the half-width of the garment. Many of the extant smocks and shirts we have of English (and even Italian) design use bands in lieu of “broader” embellishment. These bands may incorporate curving vinework within the confines of the band, or use a geometric pattern within the confines of the band. This does not seem to be a common design aesthetic for headgear (although there is at least one example), and this may be due to the three dimensional nature of the pieces altering the layout of the of the design.

There are other consistencies throughout the fashions of monochromatic pieces during this time. One of the most unusual for the modern eye to grasp is the sheer density of the designs. While a modern eye may see white space as a necessity to “set off” the image, the Elizabethan eye seemed to see white space as a blank to be filled. The design even travels off of the edge of the piece, being worked right up to the margins. This is done both with embroidery and with metal accents. Spangles, or “oes”, small disks of metal, are frequently applied to the garments worn on the head and jackets; metal bobbin lace was often applied as well, even after an item has been elaborately worked.

Fills stitches can also be considered as closing up the white spaces; geometric patterns can be used for effect to create a variety of densities; stitches like detached buttonhole and trellis may fill in a shape completely, and seed and speckling stitches give a variety of shading to a piece, which may mimic the woodcut template from a Miscellany. Once again, it is important to remember that stitches may vary within a given household, or “shop”. The difference between a seed and a speckle may be merely in the hands of the embroiderer carrying out the work.

Many stitches can be used to execute monochromatic embroidery. We frequently see stem stitches being used in outlines, but one can also find buttonhole and blanket stitch; ceylon stitch can be used for vinework; back stitch and/or double running appear both as outline stitches and fills. Speckle and seed stitches are just two of the many ways of filling a figure. As previously mentioned, even denser stitches like trellis and buttonhole variants are seen.

A note on “Spanish work”: John L. Nevinson points out that Spanish work and black embroidery are distinctly identified on the registry of New Years Gifts. Two items from 1577 show the difference:

“By Fowlke Grevell, a smocke of camerick wrought abowte the coller and the sleves of Spanysshe worke of roses and tres, and a night coyf with a forehed clothe of the same worke.”

and

“By Julio, a cushyn cloth and a pillowbere of cameryk wrought with black worke of silke.”

Whatever “Spanish work” is, it seems distinct enough in the minds of the records keeper to be listed separately.

A note on double running: Many of the extant pieces that appear to be double running are in fact a back stitch, as a glimpse at the reverse shows. (Coif 2003.63/2, Platt Hall). While double running pieces do exist, they are by no means in the majority of extant pieces, and it is interesting to consider how this stitch came to be so closely associated with “blackwork”. Joan Edwards points out that prior to the 1950s, double running was not considered a “blackwork” stitch. Mrs. Archibald Christie counts it among canvas work stitches; Louisa Pesel includes it in “Far Eastern” stitches; and Mary Thomas associates it with Assisi and Romanian work. Jane Zimmerman points out that double running only became known as the “Holbein Stitch” in the 1800s, and the term was popularized by the Royal School of Needlework only in the 20th century. It seems likely that the 20th century association of double running and blackwork, due in part to its revival in the 1960s and 1970s, is responsible for this.

It is possible that artists each put their own “spin” on monochrome embroidery. Hans Holbein, Hans Eworth, George Gower, Lucas Horenbout, Master John, and Cornelis Ketel, all represent monochrome embroidery differently from each other in paintings. Now, it is possible that since, for example, Holbein painted the wealthy elite, that all of their clothing may have been embroidered by the same group of embroiderers who did the same thing. The artist may be accurately reflecting the work as done in an individual household or shop. However, different artists seems to interpret monochrome embroidery different across their paintings. The works of Hans Eworth show a blackwork which matches the rest of his paintings, and yet, is different than that of George Gower, and different again from Hans Holbein.

Linen (processed from the flax plant Linum usitatissimum )is the primary ground for this embroidery, and the thread itself is mostly silk (from the silkmoth Bombyx mori) . There are some examples of monochrome jackets worked in wool, and this may be due to several factors: wool is less expensive, and a jacket would require many more yards than a coif; perhaps wool is thought to be more durable; and it is possible that, due to Elizabeth I’s emphasis on the English wool market, that it was a matter of patriotism and access. The silk thread used appears to be both flat silk (unreeled), and spun silk. It is unknown if the appearance of flat or spun may be artifacts of the stitches and the embroidering—some of the stitches could put a twist in the thread during their execution; likewise, some stitching may untwist or give the spun silk a flattened appearance. It is probably likely that both were used, depending on access and the needs of the embroiderer at the time. Once again, there was no “how-to” manual, and individual households made decisions that met their needs.

While there certainly were professional embroiderers in late 16th century England, George Wingfield Digby points out that coifs and nightcaps are most likely the work of private hands, as these items were “intimate”, being mostly worn at home and in the presence of family members (although not slept in, since that would destroy the fine embroidery). The line between professional and “amateur” is a blurry one; Digby chooses to use the term “domestic”, rather than amateur, because the skill level between the paid embroiderer and the private lady can be so hard to distinguish. Elizabeth I’s ladies-in-waiting were known for their skills in needlework and embroidery, and Elizabeth herself often embroidered gifts as a young woman.

A note on cultural significance: As we have discussed earlier, the Reformation in England directs energies away from ecclesiastical decoration, and concentrates more of self-decoration. Attempts to flout sumptuary laws and “rise into place” were often accentuated by elaborate embroidered items, showcasing the flamboyant in an attempt to gain Royal favour. Items embroidered with black silk appear in the New Year’s Gifts Records as early as 1561. In every year on record during her reign subsequent, there are always many embroidered items, including “black silk” and “black worke” embroidered items. Lisa M. Klein points out that the value of these embroidered pieces may not be based solely on their intrinsic and monetary value. She argues that gifts of needlework are often a part of a complex social exchange, in which exceptional embroidered items (either done by or paid for by the giver) are given with the hope of a return favor from the Queen. The giving of these high-end luxury items may place an obligation upon the Queen that she would feel compelled to repay, although this was not always the case. Klein observes that this “shows women as active participants in cultural exchange, using their material objects to forge alliances…subjects as well as the queen were able to manipulate the occasions of gift-giving to promote self-interested social relations” (Klein, 1997). Elizabeth I herself is known to have embroidered gifts of book covers for her father Henry VIII and his wife, Queen Catherine Parr, and it is therefore likely that Elizabeth would have understood the subtle messages involved in exchanging embroidered gifts.

Return to Table of Contents

Conclusion

Seemingly simple, the art of monochromatic embroidery as expressed by the English embroiderers during the reign of Elizabeth was surprisingly diverse and complex. From it’s humble geometric origins in the Islamic empire, “blackwork” crossed a continent and found a new home on the plain shores of small island. Under a Virgin Queen, it grew into a magnificent form of art, worn by the top tiers of society, showcasing a new “purely English” identity. It would be outshone in the coming centuries by polychromatic masterpieces, but for a brief time, monochrome embroidery took center stage as the pinnacle of a craftsperson’s skill.

Return to Table of Contents

Appendix: Extant Monochromatic Pieces Personally Examined by the Author

At the Clothworkers’ Centre of the Victoria and Albert Museum:

Coif T.54-1947

Nightcap 814-1891

Coif T.320-1979

Coif 756-1902

Coif T.53-1947

Boy’s Shirt T.112-1972

Handkerchief T.133-1956

Smock T.2-1956

Forehead cloth T.26-1975

Nightcap T.10-1950

At Platt Hall, Manchester City Galleries (the Gallery of Costume collection is not currently available online:

Forehead Cloth 2003.65

Coif 1999.56

Nightcap 1959-271

Coif and Forehead Cloth 2003.63/2

Smock 2003.76

At the Museum of London:

Jacket A21990

Jacket 59.77a

Smock A21968

Skirt 59.77b

At the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston:

Coif and Forehead Cloth 43.244a-b

Coif 1996.51

Return to Table of Contents

References

Arnold, J. (1988). Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe unlock’d . Leeds: W. S. Maney and Son, Ltd.

Arnold, J. (2008). Patterns of Fashion 4: The cut and construction of linen shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear, and accessories for men and women c. 1540-1660. London: MacMillan.

Beck, T. (1974). Gardens in Elizabethan embroidery. Garden History, 3 (1), 44-56.

Brooks, M. M. (2004). English embroideries of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum. London: Jonathan Horne Publications.

Carey, J. (2012). Elizabethan stitches: A guide to historic English needlework . Devon: Carey Company.

Digby, G. W. (1963). Elizabethan embroidery. London: Farber and Farber.

Edwards, J. (1980). The second of Joan Edwards’ small books on the history of embroidery: Blackwork. Surrey: Bayford Books.

Figural representation in Islamic art. (n.d.) In Heilbrunn timeline of art history.

Hentschell, R. (2008). The culture of cloth in Early Modern England: Textual constructions of a national identity. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Jaster, M. R. (2006). ‘Clothing themselves in acres’: Apparel and impoverishment in medieval and early modern England. Medieval Clothing and Textiles, 2, 91100.

Kirtio, L. (2012). ‘The inordinate excess in apparel’: Sumptuary legislation in Tudor England. Constellations, 3 (1).

Klein, L. M. (1997). Your humble handmaiden: Elizabethan gifts of needlework. Renaissance Quarterly, 50 (2), 459493.

Leed, D. (2010.) Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe uploaded. DressDB.

Librarius. (n.d.) The miller’s tale: lines 125-162.

Mellin, L. (2008). A lady’s embroidered coif of the late 16th/early 17th century.

Morrall, A., & Watts, M. (eds). (2008). English embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1580-1700: ‘Twixt art and nature. New Haven: Yale University Press.

NeCastro, G. (2011). The miller’s tale.

Nevinson, John L. (1938). Catalogue of English domestic embroidery of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Nevinson, J. L. (1940). English domestic embroidery patterns of the 16th and 17th centuries. The Twenty-eighth volume of the Walpole Society, 28 (1), 114.

Nunn-Weinberg, D. (2006). The matron goes to the masque: The dual identity of the English embroidered jacket. Medieval Clothing and Textiles, 2, 151174.

Quinton, R. (2013). Seventeenth-century costume . London: Unicorn Press Ltd.

Reynolds, A. (2013). In fine style. London: Royal Collection Trust.

Smith, G. (2009). The chemistry of historically important black inks, paints, and dyes. Chemistry Education in New Zealand, 12-15.

Trevelyon, T. (1608). Miscellany.

Victoria and Albert Museum. (1953). Elizabethan Embroidery. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Wace, A. J. B. (1933). English embroideries belonging to Sir John Carew Pole. The Twenty-first volume of the Walpole Society, 21 (1), 4366.

Zimmerman, J. (2008). The art of English blackwork.

Return to Table of Contents